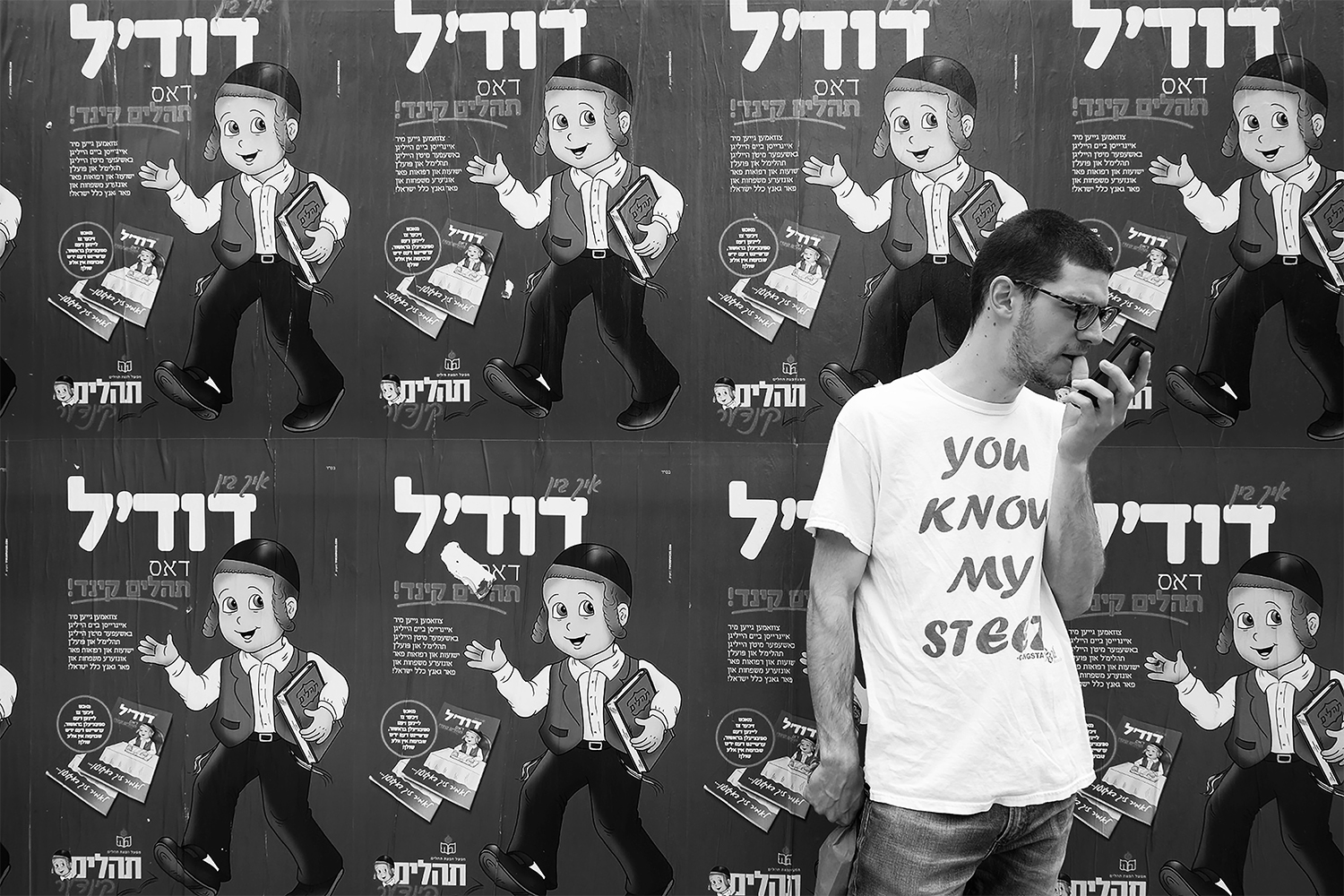

In a secluded corner of Prospect Park, Tzvi Levine, a 22-year-old resident of Kensington, Brooklyn, ground some weed, made a joint, took a puff, and began strumming his guitar while improvising a song. The sinking-sun shone golden on his clean-shaven face, the trees cast long shadows, and Levine’s Nike sneakers tapped to a beat. He looks like an average Brooklynite: jeans, a white t-shirt, Buddy Holly-glasses frames. He sat on a fallen tree trunk crossed diagonally over poison ivy and rotting foliage. A plastic shopping bag beside him contained a cucumber and iceberg lettuce. Levine often brings raw foods with him to enjoy their “pureness”, and occasionally, he’d take a bite. Perched next to him, Yoni Krakauer, Levine’s friend of only a year, removed his kippah before reaching for a smoke. The two meet here to unwind. There are no rules to follow, and they can speak freely. Levine notes that it’s a place where he can feel in-touch with nature.

During the day, Levine spends time with his nine siblings in his parents’ Jewish Orthodox home: he sings on the couch, plays games, or reads books when they return from school. He currently has no day job, and is largely supported by his parents by means of food and housing.

At night, Levine is a hip-hop performer, attending open mics in Brooklyn, making connections, and hoping to gain popularity as a white artist in a predominantly black community that created hip hop as a reaction to oppression from white people.

Levine was raised Orthodox, but decided to forgo his religion after being expelled from his mesivta, or Jewish high school, at the end of 12th grade for poor attendance. “I didn’t like authority there,” said Levine. “I hated the way that the rabbis had power and I hated the way that they knew more than you. There were ten-hour school days and at one point we slept in dorms.”

As Levine grew up, he encountered a disconnect between the strict laws of Orthodoxy and his own interests. Levine had grown up in a musical family, and had taken interest in non-Jewish music that he heard away from school and his home. “When I was in 9th or 10th grade, I felt repressed from the school and the class I was in because they forbid us to listen to non-Jewish music, even if it was “clean,’” Levine said. During this time, Levine discovered hip hop music. “A friend of mine put Not Afraid, an Eminem song, on my iPod Nano,” said Levine. “He found some way to not make it show up unless you searched for it.”

Not Afraid was the catalyst to Levine’s interest in hip hop. He became interested in the technicalities of rhyming to rhythms and spent time trying to compose his own similar work. As his interest in the non-Jewish world increased, Levine spent less time attending classes, and thinking more about life outside Judaism.

After leaving school and choosing not to continue the path to yeshiva, Levine’s parents became increasingly unhappy, ultimately banning him from their home. Levine was sent to live with his grandparents in the neighborhood, picking up a telemarketing job after being encouraged by his grandfather. Levine has no current intention to attend college. He has held a series of part-time jobs since leaving school, but is currently unemployed.

Living in the basement of his grandparents’ house gave Levine the freedom he lacked in his own home. “That’s when I was able to do whatever I wanted,” said Levine. “I really got into hip hop then because I was free to listen to non-Jewish music. I also started watching porn and smoking weed.” Growing up in an Orthodox community, Levine sheltered from the outside world. “I grew up without a TV or movies, and no non-Jewish music whatsoever,” said Levine. “All of these rules would have stayed with me forever, but I just stopped following them.”

Levine would sneak out the back door at night, unknown to his grandparents, but made sure to be home for Shabbos each week, putting on a kippah before entering his home.

Levine’s telemarketing job allowed him to save money to buy recording equipment. After being allowed to move home over a year later, Levine took over the empty garage in his backyard. He began to create his own music inspired by the hip hop he had listened to. “I made a song, and it was like a white-boy knockoff of Eminem,” he said. “It was about being different.” Songwriting and performing was easy for Levine. “I grew up singing, and I taught myself to play guitar,” he said.

After posting the song to an online hip hop forum, Levine was contacted to attend an open mic. He continued to write songs inspired by artists like Kendrick Lamar and MF Doom, often with explicit lyrics that contrasted the tenets of his upbringing.

Levine chose to tell his father about his interest in hip hop, but not to his siblings. “I told my dad that I could write rap really well,” said Levine. “But he just asked what my back up plan was going to be.” After showing his father the music he had written, he started to take his son more seriously.

Levine’s father, who recently graduated from NYU’s Silver School of Social Work, has been supportive of his music and non-Jewish interests. “I think my dad is sort of proud of me as a hip hop artist in certain ways: he’d show non-Jewish people what I’m doing,” Levine said. “He even brought me into his class once to lecture about weed.”

Levine’s mother takes a more hands-off approach to her son’s diversion from Orthodoxy. “My mom doesn’t say much about what she thinks of me because she’d rather not learn about what I’m up to,” Levine said. “She’s going to get hurt by what I say or what I do with my life because she’s afraid.”

After establishing himself back at home, Levine started to attend open mics in Bedford Stuyvesant or East New York. He became enamored with the community. “I was able to meet a lot of people who encouraged me and gave me connections,” Levine said. But even as he tries to be an optimist about his experience, he’s also had trouble fitting in. At a hip hop party in East New York, a woman took the stage to criticize Levine for being white. “She singled me out and started talking about me saying that I was coming there to take their culture,” Levine said.

“Most people who don’t like me aren’t interested in seeing me as a person, but then they realize I’m respectful, and that I grew up in Brooklyn just like them,” Levine said. “I’ve had a lot of bad experiences, but the good ones outweigh them.”

Levine has found an expanding group of people who accept him and hope to help him gain recognition within Brooklyn’s hip hop community, but when he returns home to Kensington, he is happy to blend into the crowd. “Kensington and Borough Park are like Manhattan,” said Levine. “It’s so diverse there, and nobody cares who you are. Sometimes if I want a favor, I’ll make it known that I’m Jewish by saying something in Yiddish. Otherwise, everyone minds their own business.” Even Levine’s siblings have become used to him. “My baby sister just thinks that I sleep all day,” he said. “When I’m not at home spending time with my family, they don’t question where I am.”

Living a double-life between hip hop and family life has helped Levine evolve his musical style. “My music doesn’t usually discuss being Jewish, but the sincerity in which I sing is reflective of my upbringing,” said Levine. Levine realized that hip hop could include more than rap: he heard performers sing at open mics and soon adapted that style to fit his own voice.

At a Bedford Stuyvesant open mic that Levine hadn’t attended before, he approached the crowd with a song that predominantly relied on vocals and chorus, rather than rap. At the end of his song, Levine was accompanied by a loud ovation.

Moments like these encourage Levine to continue writing and performing. “It’s a life direction, not a money-making career,” said Levine. “I don’t see it taking me anywhere, but if it does, I’d love to get enough recognition to allow me to work with Kendrick Lamar or Anderson Paak. I enjoy collaboration because I want other people’s influences. It’s about community.”

At Prospect Park the following day, Levine brought a cucumber to enjoy alongside music and weed. Krakauer, who has known Levine for only a year sat beside him. Krakauer isn’t a fan of hip hop, but still supports Levine. “He has beautiful melodies and chord progressions, so I wonder why Tzvi even raps at all,” Krakauer said, suggesting that Levine’s talents lie in the “jam-sessions” he and Krakauer engage in. Levine plays guitar, and the two of them sing together.

“It’s very difficult for me to figure out how hip hop and Judaism mix because I don’t see it very clearly,” Levine said. So, Levine uses this time to find contentment and reason in a segmented life. Despite no longer being a practicing Jew, Levine remains spiritual on his own terms. “My spirituality is happiness, and from playing guitar,” Levine said. “It’s contentment from being grateful for everything you have.” For Levine, happiness comes from enjoying the things around him in their most natural state: nature, raw food, air. “I don’t connect to a specific god anymore,” he said. “The world is perfectly made for us to live in.”

When Levine returns home, he sleeps on the bottom bunk of a room shared by three of his siblings. He drapes a blanket from the rim of the top bunk, creating a closed-off space for him to relax. “This is the only private space I have in my home,” said Levine. He has no plans to move out of his parents’ house, and has no intention of quitting hip hop anytime soon. “I’m a very simple person,” said Levine. “I sleep and eat at home, so I don’t need much money.”