Dr. Lois Bookhardt-Murray said she has been treating opioid addiction for more than 30 years and is still haunted by patient overdoses.

“A patient came in and it was clear that they were slipping into a coma,” she said. Bookhardt-Murray, the chief medical officer at Morris Heights Health Center (MHHC) in the Bronx, said she administered naloxone, the lifesaving medication that blocks receptors that carry drugs to different parts of the body, reversing deadly overdoses. “The patient came back right away,” she said.

Bookhardt-Murray said that over the past decade, the opioid epidemic has become an increasing danger to public health. “We used to see rampant drug use, opioid use, mainly in in poor communities. But that has now extended into the suburbs,” she said.

Bookhardt-Murray said that while the New York City and New York State health departments provide substantial tools to combat opioid deaths, everyday New Yorkers do not enroll in free naloxone programs because of stigma, a lack of grassroots outreach and fear of administering naloxone. Bookhardt-Murray said having more people carrying naloxone is crucial because “young people are dying like never before.” The lack of trained New Yorkers, along with the uptick in fentanyl-laced opioids and increased opioid use among adolescents is what Bookhardt-Murray said could contribute to the worsening of the opioid epidemic in 2018.

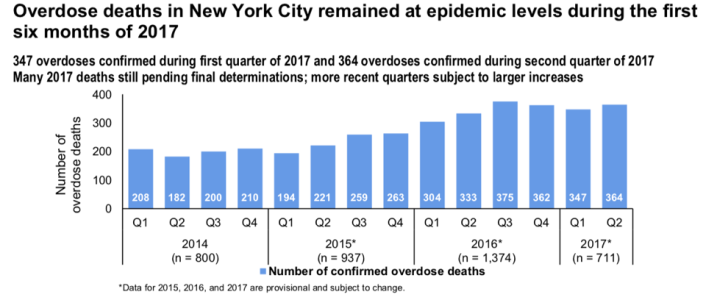

As 2017 comes to a close, preliminary data from the New York City and New York State Departments of Health suggest that this year could be the deadliest for opioid abusers in New York. New York State Department of Health (DOH) representative Jill Montag said that 2017 data is still being collected, but stopped short of saying that the numbers will increase. There were more than 3,200 opioid deaths across the state in 2016, according to city and state provisional data.

Naloxone became available without a prescription in 2006, Montag said in an email. Naloxone is available in a nasal spray, a manual injection and an autoinjector. Montag said that the state-run program provides free naloxone and training through 500 community partners that include harm reduction centers, hospitals and schools. She said that New Yorkers can also purchase naloxone at pharmacies around the state.

Bookhardt-Murray said that training more everyday people to carry and administer naloxone will save lives. But not enough people are involved in the program, she said.

Over email, New York City DOH representative Christopher Miller said, “New York City is experiencing that same epidemic that we’re seeing nationally – someone in New York City dies of a drug overdose every seven hours.”

Miller said that the city distributed more than 45,000 naloxone kits in 2017. He said the city has done extensive outreach, investing $38 million in opioid addiction prevention and treatment this year. He said in order to reduce opioid deaths, the city must help educate the public and reduce stigma around addiction.

In an email, Montag said, “New York State continues to take aggressive steps to combat the heroin and opioid epidemic, and expanding access to naloxone is part of that approach.” Montag said that Governor [Andrew] Cuomo has invested $200 million in the fight against the opioid epidemic this year alone – $7 million of which covered the cost of naloxone. Montag said the state recently launched a co-payment assistance program to provide access to naloxone from pharmacies at little or no cost to the individual.

Montag reported that since 2014, the state has trained more than 140,000 community members. However, naloxone was administered only 2,653 times by community members in the same time period despite an increase in overdose deaths.

Bookhardt-Murray said that the number of trained naloxone administrators is still not high enough.

“The uptake is not exactly what it should be in New York State, even among [healthcare] providers,” Bookhardt-Murray said and continued, “The city and state have provided a lot of resources and we have yet to make sure that those resources are put to good, widespread use.”

Bookhardt-Murray said fear is a large hurdle for new recruits and even for trained individuals.

Mark Hardison, a recovering addict, said he received naloxone while undergoing treatment last year. Despite undergoing training, Hardison said he is still apprehensive about how he would handle an actual overdose situation. “You wonder: ‘What would I do?’”

Dr. Katherine Austin, the medical director of community-based services at Morris Heights Health Center (MHHC), said that sentiments like Hardison’s are common, even among those who have completed the hour-long training she provides. “There’s a fear of making a mistake, of not doing the right thing or harming the person,” Austin said. She said that naloxone cannot hurt anyone and that even administering naloxone to someone who was not overdosing would not cause injury to the patient.

Other issues that concern potential candidates for naloxone training programs include legal ramifications and safety.

Bookhardt-Murray said that people are concerned about needle sticks that could transmit diseases like HIV and Hepatitis, but that most non-medical professionals use the nasal spray.

Montag said that the state was not aware of any accidental sticks. She said the state minimizes the risk by providing safety syringes that have a mechanism for covering the needle after use and non-latex gloves to responders.

Montag and Miller said that Good Samaritan laws protect community members from liability upon administration of the medication, but Bookhardt-Murray said that carrying injectable naloxone still puts individuals at risk legally. Some cops don’t know about naloxone, so if you have needles on you and you’re suspect, you could get in a lot of trouble.”

Beyond fear, Bookhardt-Murray and Hardison said that New Yorkers are not invested in saving the lives of opioid abusers unless they know someone who is addicted to drugs or has died from an overdose. Bookhardt-Murray and Hardison attributed this behavior to stigma around drug abuse.

Hardison said he talks to people about the naloxone program, but is met with superficial interest. “It’s one more thing to carry…and one more thing to think about.”

Adrienne Upton, a native of Dutchess County, said in a Facebook message that she is concerned about injury as a result of administering naloxone. Upton said that addicts do not wake up grateful to be alive. “There begins the downward spiral of the citizen,” she said.

Such sentiments are typical, Bookhardt-Murray said. She said individuals who are not personally impacted by the opioid epidemic are not generally concerned about becoming trained to administer naloxone.

Bookhardt-Murray said that targeted, grassroots outreach would reduce stigma and increase naloxone program participation. “I’m African-American. I know that churches are always our first go-to,” Bookhardt-Murray said and continued, “If you can get ministers on board, if you can train church people and get them interested, then it works.”

Bookhardt-Murray’s advice to the City and State Departments of Health: In order to minimize overdose deaths in New York, target homeless shelters and high schools for more education and training. “We need to get people who are likely to get into contact with people who are overdosing, she said.

Bookhardt-Murray said that every high school student in the state should be trained. She said it will create a mass of young, altruistic, naloxone-trained New Yorkers.

“We’re up against an industry of drug sales. We’re up against a machine,” she said. “Naloxone has got to become cool to use. It’s got to become the cool thing that saves your friend’s life.”