Khin Thaw Win works as a waitress five days a week at a local restaurant in Buffalo, New York. It’s not a job she’s passionate about, but for the last 8 years, jobs like these have allowed her to do the work she truly cares about: helping low-income women navigate pregnancy and labor.

While she’s working, she’s also on-call for her job as a doula, or a non-medical companion that serves as an advocate during pregnancy and labor by providing both physical and emotional support to mothers. The 25-year-old is part of the Priscilla Project, a program that works to provide healthy birth outcomes for women who cannot afford the price of private doulas in Buffalo, New York.

“I would love it to be my [full-time] job, but it’s not possible,” Win said. “I am on-call most nights in case one of my clients go into labor, and I work during the day.”

Win and other doulas who work with low-income mothers are not able to work as doulas full-time because non-profit organizations like the Priscila Project are unable to afford to pay their workers full time. Even though Win works as a doula for forty hours a week, she is not able to call it her full-time job because the Priscilla Project relies on services like Medicaid to pay their doulas.

Doulas–who at private firms cost between $1600 to $2000–are typically not covered by insurance companies, making them a luxury for those who need them the most.

As maternal mortality rates in the United States for mother’s increase, studies have found that doulas can help improve birth outcomes for mothers. For refugees and low-income women, who face higher rates maternal mortality, doulas have been shown to vastly improve birth outcomes, and greater access to doulas can help improve maternal mortality rates, especially in New York, where maternal mortality have doubled since 2001.

In April 2018, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced an initiative to expand Medicaid to cover doulas based on the recommendations from a task force of experts based exploring racial disparities in maternal mortality.

The state’s original goal with these initiatives was “to target maternal mortality and reduce racial disparities in health outcomes,” according to the statement from the New State Governor’s Office. Erie and Kings County were chosen to be the first two places to pilot the program because they have the state’s highest number of Medicaid births and maternal and infant mortality rates.

Erie County in particular has been experiencing rising rates of poverty, and 30% of women living in the area are considered below the federal poverty guidelines.

“Disparate outcomes are usually caused by systemic problems,” Danielle Laraque-Arena, one of the co-chair’s on the task force, said. “They are pockets of concentrated poverty and poor health outcomes [in New York]. Erie County was probably picked because it is one of those areas.”

However, in Kings County also known as Brooklyn, where the population is 34% African American, the doula program failed to launch in time because not enough doulas signed up because of pay concerns. Regina M. Conceição, a doula based in Brooklyn, said the program offered doulas in the area $200 for their services during labor and delivery.

Kings County has since been rechristened as “phase two” of the program, with “phase one” launching in Erie County on March 1st, where the population is 14% African American and 20% refugee and immigrants. Twenty-four doulas currently signed up as part of the program, including Win.

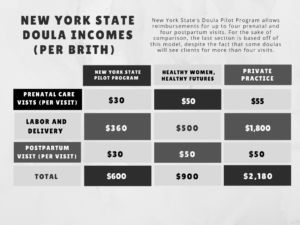

In Erie County, the payment is now $360 per birth and $30 for four prenatal visits and four postpartum visits. Conceição believes this increase is a result of the uproar in Kings County.

Even with this increase in compensation, doulas currently working in Erie County and Kings County do not believe that the Medicaid reimbursements are enough for doulas to work full-time caring for low-income women.

Even with this increase in compensation, doulas currently working in Erie County and Kings County do not believe that the Medicaid reimbursements are enough for doulas to work full-time caring for low-income women.

“It’s not a livable wage,” Conceição, who works with low-income mothers via her organization Passions for New Beginnings, said. “To make 35,000 dollars, you would have to attend about 52 births [on the Medicaid program]. You can’t do it. You would have no life whatsoever.”

Conceição mentioned that Healthy Women Healthy Futures, an organization that provides free birth and postpartum doulas across New York City is able to pay better than the Medicaid program does, which means doulas who are interested in focusing on low-income communities are less likely to participate in any Medicaid program that comes to New York City.

“Doulas were like, ‘hell no, I’ll do this on my own I’ll work for Healthy Women, Healthy Futures, where they’re going to pay me better,’” Conceição said.

It’s not uncommon for Medicaid programs to give less compensation than what a doctor would make in private practice but it is still a cause for concern for Conceição, who believes that these initiatives should be valuing the work that goes into being a doula more.

“I’ve been a doula for 19 years and [getting doulas a living wage] this has been my fight for 19 years,” Conceição,41, said. “Medicaid needs to be doing what it’s supposed to do instead of trying to undercut doulas.”

Win and Conceição both share a passion for making doulas more accessible to all women; this is what motivates Win to work in the Medicaid reimbursement plan, even if that means she will be paid less.

Win mainly works with refugees at Priscilla, specifically ones who speak Burmese, her native language. Like Conceição, Win works for an organization that is able to pay her more than what the Medicaid reimbursement plan offers, but it still isn’t enough to cover her basic expenses. This month, she has helped with six births alone; she says that the number of births she assists with fluctuates, so she never really knows how much she will make per month.

Sometimes, Win will even provide services that are not covered by Medicaid. Even though this means she has to work another job to keep herself financially stable, Win thinks that it’s worth it because what she does can help save lives.

“Having a doula in the labor room can make a change,” Win said. “When you have a doula, clients are able to have their birth on their terms, which means less pain and more healthy babies.”

Brenzella (Della) Williams, 65, is another doula participating in the pilot program. Her decision to become a doula came after being laid off from her previous job in the healthcare industry two years ago. Instead of retiring, she decided to get certified as a doula.

Currently, four out of Williams’ five clients are using Medicaid reimbursements to pay for her services. While she is glad she is able to help these women, she wishes that the compensation was enough to be a full-time job. While Williams herself is able to afford to just be a doula because of her retirement fund, she noticed that a lot of her peers decided to not participate in Erie County’s pilot because they were worried about making ends meet.

“I know a lot of doulas who aren’t even touching the [program] because of the low reimbursements,” Williams said. “If you were participating in the reimbursement plan, you would have to have another job.”

Since the program is still in its infancy, Williams believes that the initiative needs to do a better job of outreach for women who might use these services but mainly needs to reach out to more doulas by giving them a higher pay incentive.

“[The pilot program] is asking for a lot more than what you might have to do as a doula,” Williams said. “For me, there’s a need for it, so I enjoy being there for the client, but others are not as willing because it can’t be a full-time job.”

For both Williams and Win, being a doula is an incredibly rewarding experience; one that they feel lucky to be a part of every single day–they just wish that they could afford to help combat the high mortality rates without having to worry about how much they are benefiting from it.

“Medicaid reimbursements, even for providers is low,” Williams said. “It’s our hope that once the program starts and the pilot is over, they’ll look to reconsider how much they are paying doulas.”