New York City is a ghost town. The empire state is the country’s epicenter for covid-19, the illness caused by SARS-CoV-2 (one of many coronaviruses), with a total of 335,000 infections as of May 9, according to Intelligencer. The Big Apple alone is enduring 178,776 cases, according to The City. Now, sidewalks once littered with pedestrians are barren in the wake of the novel coronavirus. It is this gray shell of the city that never sleeps that Ayomide Falola, who requested her name be altered for confidentiality reasons, must travel through to get to work. As a cashier at CVS, her job is what the current health pandemic has determined to be essential to the continuation of society.

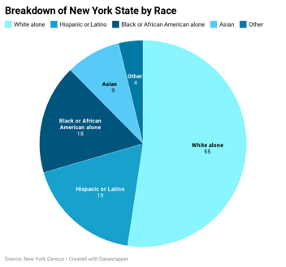

Nationwide, but in New York especially, the novel coronavirus is disproportionately impacting black communities, killing black people at a much higher rate than others. Issues of structural racism within various facets of society, such as socioeconomic statuses, the healthcare system, and law enforcement create the grounds for the virus to mushroom among the country’s most vulnerable populations.

Falola’s socioeconomic status denies her the privilege of quarantining at home. Five times a week, the young Nigerian immigrant must brace the dangers of outside to get to work. Quickly, she noticed a trend among the few people that were still moving around the city.

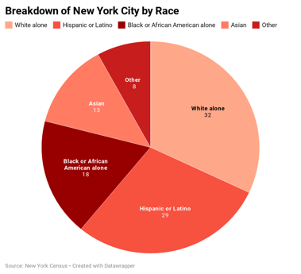

“The only time I see white people is when they are coming in to buy stuff,” she stated. Her stint at CVS has not been a long one, she began working on March 13, but the start of her job coincided with the implementation of extreme precautions against the spread of covid-19, such as a statewide lockdown and halt on all non-essential business. Within a very small window of time, the young cashier has seen firsthand the various ways that racism and covid-19 overlap.

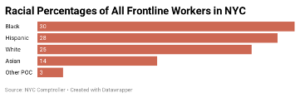

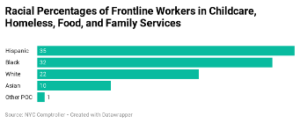

“The overnight people are mostly black,” she said. In New York City, 30% of all non-governmental essential workers are black, according to data released by the New York City Comptroller. Additionally, 53% of the city’s essential workers are foreign-born. Frontline jobs in industries such as childcare and grocery stores are rarely well paying. In 2017, full-time home care aides earned an average of $27,000 in New York State, according to the city Department of Consumer and Worker Protection.

Not coincidentally, such positions are usually filled by those most in need of money. One-third of front-line employees come from low-income households, Gov. Cuomo stated. Due to generational income inequality, in 2014, the average income for white families in New York state was “77% greater than the average family income for black and 93% greater than the average for Latino families,” according to the Fiscal Policy Institute.

In Falola’s case, the young Nigerian immigrant needs the hourly pay of $15, New York’s minimum wage, in order to afford her rent and purchase groceries. In the blink of an eye, she has been forced into a position where she has to compromise her health, and possibly her life, in order to survive. Her job has not made this any easier.

“We get one mask a week,” the cashier exclaimed. In the midst of the pandemic, protective face masks have become a sort of currency. Public panic about the virus reached a fever pitch, causing masks to completely sell out in various locations. The national Center for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that masks, in combination with other preventive measures, such as social distancing, or maintaining a minimum six-foot distance from others while in public, should be worn to slow the spread of the virus.

There are a number of self-checkout machines at Falola’s store, therefore her job should not entail that she come in direct contact with customers. Yet, complaints and negative reviews from customers that were denied their requests to be rung up by a cashier have caused her bosses to mandate that employees grant customers their requests. “Why am I interacting with these people just because they don’t want to work self-checkout?” she exclaimed.

Additionally, as more of her coworkers use this time to take their sick days, or simply quit, her store is now understaffed, according to her. As one of the few remaining employees, her daily workload has increased significantly.

For all the trials she endures at her job, the cashier is not receiving much in return. Her store offered hourly employees an extra $300 as compensation for those that worked through the month of April.

The workplace is not only setting where these disparities prevail. Falola commutes from her apartment in Brooklyn to Lower Manhattan and on the train, she witnesses a racial makeup similar to that of her job. “Since I started working, I’ve seen three white men on the train” she said.

Inside New York’s transit system, all of the city’s systematic inequalities amount to who is sitting, or sleeping, on the train. “The average frontline worker will spend 45 minutes traveling to work each day and another 45 minutes traveling back home,” according to the comptroller. Using public transportation greatly increases one’s risk of contracting covid-19, as the virus can survive on surfaces for hours.

The vast majority of essential workers must brave train cars in order to get to work. According to the comptroller, 28% of the city’s frontline workers reside in Brooklyn. Queens comes in second, contributing 22% of workers. Both boroughs are predominantly working class and with a significant percentage of black residents. Such factors directly contribute to the impact the coronavirus is having on these communities. With a whopping 53,692 infections, Queens is the borough with the most covid-19 cases, according to The City. The most deaths have been in Brooklyn.

“The hard thing for me was that I had to ride the train,” said Ileri Jaiyeoba. A young, black college graduate, Jaiyeoba recently quit her job as a personal aid to a woman with disabilities. Her job description entailed duties such as helping her boss get ready in the morning and helping her use the restroom, making the prospect of social distancing obsolete. The train was her tipping point. “I was running into instances where a very sick person is coughing in my direction,” she said.

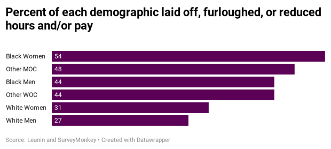

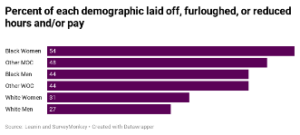

Prior to her decision to quit, the coronavirus had already begun to impact her financially. What was once a job she did two times a day was cut back to once a day. Her experience is not unique to her, as “black women are twice as likely as white men to say that they’d either been laid off, furloughed, or had their hours or pay reduced because of the coronavirus pandemic,” according to a survey LeanIn.Org and SurveyMonkey conducted on 2,986 people.

In addition to loss of income, many black women are losing their lives to the coronavirus. “Black women are overrepresented among adult care workers relative to their share of working adult women in both home care and institutional care settings,” stated the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

The New York University senior was painstakingly aware of this trend prior to quitting. As a young black woman, Jaiyeoba feared the many ways in which her identity made her more susceptible to covid-19, but she remained mindful of the other black women experiencing the same thing. “I was scared to quit because I knew that once I quit, she would be dependent on this black elderly lady who has like a lot of kids who also commutes from Brooklyn,” she stated.

Now in the aftermath of her decision, Jaiyeoba is angry. The loss of her primary income has weighed heavy on her mind and has caused her to reflect on the ways structural racism has allowed the virus to impact black communities. “There is never a time for black people to grieve,” she stated. “There’s always another the battle to fight.”

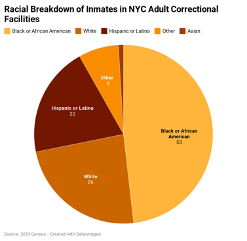

New York’s prisons and jails serve as another battle ground in which black people combat covid-19. “Certain communities get targeted for policing and this is intersected at race and class,” said Lydia Pelot-Hobbs, a postdoctoral fellow with the Prison Education Program at NYU. “We know people are selling drugs all over New York City, but the police do not go to Columbia, they instead focus their energies in parts of the Bronx and Brooklyn,” she explained.

Racial policing has been very evident during the pandemic. Viral images from the beginning of May showcase a tale of two parks. A recently opened park in the West Village was littered with white park goers congregated in close proximity to one another without masks or any other protective gear. Another image from the same park showcases an officer handing out surgical masks. Meanwhile, video footage from Brownsville, Brooklyn showcases police chasing and arresting residents for standing in front of their apartment buildings.

Statistics released by the Brooklyn district attorney’s office reveal that out of the 40 people arrested for social-distancing violations, 35 people were black. “More than a third of the arrests were made in the predominantly black neighborhood of Brownsville. No arrests were made in the more white Brooklyn neighborhood of Park Slope,” according to the New York Times.

Such racial criminalization determines the demographic makeup of jails and prisons. In New York state alone, black or African American adults make up 53% of the total population in correctional facilities for adults, according to the 2010 census.

Prisoners are especially vulnerable to contracting the virus. Due to the set-up of their confines, social distancing is not an option. “They’re in settings that absolutely facilitates, in a dramatic way, the transmission of the virus,” stated Robert E. Fullilove, Associate Dean for Community and Minority Affairs, professor of Clinical Sociomedical Sciences at Columbia University, and senior advisor of the Bard College Prison Initiative.

“They are in facilities where you got 50 folks jam packed together in the same dormitory,” he said. Additionally, hand sanitizer is widely banned, as it is considered contraband, and access to toilet paper and many other essentials are limited. Outside of the coronavirus, each year spent in prison takes two years off of an individual’s life, according to a report by the Prison Policy Initiative. The arrival of covid-19 simply adds onto a list of health concerns and makes the prospect of death even more prominent.

Prison facilities cannot bare all the blame. “Prisons incarcerate folks who aren’t in good health,” Fullilove said. New York City neighborhoods with high rates of imprisonment are likely to suffer from health problems disproportionately. There is a strong correlation between asthma rates among children and incarceration, according to the Prison Policy Initiate. “For every additional 1% of residents who had asthma in the past year in a given neighborhood, the imprisonment rate increases by 49 people (per 100,000),” the study stated.

While no direct causation has been found for these figures, factors such as environmental hazards and income inequality certainly contribute. “Prisons are simply a conduit, through which pass all of the problems that are present in the communities that are most hard hit by public health challenges,” Fullilove said.

Close confines, substandard healthcare, and a population predisposed to preexisting health conditions have already taken their toll on incarcerated people. Rikers Island has been referred to as a “public health disaster” by the jail’s top physician, with an infection rate of 9.53%. This is in comparison to an infection rate of 2.15% in New York City and 1.71% in the State, according to data from The Legal Aid Society. And not only prisoners are being impacted. As of April 20, more than 800 city correction employees tested positive for covid-19. Including inmates, there have been 1,200 reported cases and 10 reported deaths in the city’s jails, according to city officials.

Governmental responses to these staggering trends have been minimal. As of March 27, the governor’s office ordered a state-wide release of 1,110 people detained for parole violations. And on April 14, Gov. Cuomo announced that elderly prisoners who are close to their release dates will be released. Yet, not all people covered by the order have actually been released. “It is the responsibility of the local jails to release the individual,” a spokesperson for the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision stated.

“Cuomo has been colluding with district attorneys on who is less of a risk to the public with not a public health approach, but a very law and order approach,” Lydia Pelot-Hobbs explained. And Fullilove would agree. “There’s a political cost associated with doing the right thing,” he stated. “Prisoners are dealt with as if the minimum amount necessary is going to have to be done in order to not pay the price politically for having a soft on crime approach.”

A minimal reduction in jail populations is nowhere near enough to effectively combat the exponential spread of the virus among the incarcerated. And something must be done quickly, as leaders from some of the largest public defender organizations in the state have estimated that 10,000 individuals incarcerated in New York’s prisons and jails are at grave risk from the coronavirus.

Carceral activists such as Pelot-Hobbs have done what they can to enact change, but not much can be done without government action “I’ve made calls to the Department of Corrections. They simply write my message down and that’s it,” she said.

The coronavirus also brings the prevalence of housing insecurity to light. Like many others, Ileri Jaiyeoba lost her job to the pandemic. At the moment, Jaiyeoba is depending on her second job as a student researcher at NYU to get by, but when that ends on May 19, she doesn’t know how she will pay her rent. “Everything’s honestly up in the air. I don’t know what’s happening,” she shrugged. According to SurveyMonkey, when asked how long they could afford groceries and rent if they were to lose their income, “34% of black women said less than one month, versus 28% of black men, 25% of white women and 11% of white men.”

Although a citywide moratorium, or halt, on evictions is in effect until August 20, a rent freeze has yet to be announced. “The eviction moratorium is an important first step, but it is not enough to address the dire needs of hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers pushed further into housing insecurity as a result of the pandemic,” Oksana Mironova, a housing policy analyst for the Community Service Society, told New York Daily News.

The decision to collect rent is ultimately up to the individual landlord. Many have implemented their own rent freezes, but not Jaiyeoba’s. An activist and community organizer herself, she considered organizing a rent strike in her building, something that many New Yorkers have already done, but was quickly brought to a grim reality by the residents of her Bushwick complex. “There are a bunch of wealthy white people in my apartment complex. What are they going to do with a rent freeze?” she said. “It doesn’t matter to them like it would matter to me.”

Her trying experience with covid-19 has taught the young organizer a lot about community. A child of Nigerian immigrants, she comes from a cultural norm of sharing resources and being community minded. According to her, American individualism is greatly to blame for much of the tragedy caused by the virus. “You’re seeing on an individual level as people are trying to build community structures who thinks you’re disposable,” she said. “Who gets to be human in this pandemic?”

This question especially applies to America’s homeless, a group in which black people are overrepresented due to structural issues such as underemployment. Approximately 57% of the heads of household in New York City shelters are black, according to the Coalition for the Homeless. Black women in particular “constitute about 44% of those who are evicted from their homes in urban areas,” a Harvard study found. “As a result, they disproportionately experience homelessness.”

Social distancing in shelters is nearly impossible, as their needs are met en masse.

“There has always been an increased risk of communicable diseases like tuberculosis, hepatitis A, and influenza,” Margot Kushel, a professor of medicine at UC San Francisco who studies homelessness told Wired. “Covid-19 is just the newest addition to the list.”

Homelessness was already a prominent issue in New York City, as rising rent prices caused the number of people experiencing homelessness to grow to 79,000 since Mayor Bill de Blasio took office in 2014. Now, corona-induced housing insecurity is driving more people into shelters. Many inmates released from Rikers Island have wound up in a shelter, according to the New York Times.

In order to thin out shelters, state government has been moving people into vacant hotel rooms. The city has been paying an “average cost of at least $174 a night to isolate shelter residents who have symptoms or tested positive as well those potentially exposed,” the article stated.

Yet, as the subway has now shut down from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m. for daily cleanings, many homeless New Yorkers have been forced out of their lodgings. “The subways cannot be used by the homeless as an overnight shelter,” Gov. Cuomo told the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, according to NPR.

Further protections for this population are needed, and quickly. Estimates from researchers at Boston University, University of Pennsylvania and UCLA have found that “the coronavirus pandemic is likely to kill more than 3,400 people experiencing homelessness across the United States.”

Ultimately, the coronavirus is not “the great equalizer” that it is commonly referred to as. The racial disparities laden within the structure of this country must be addressed directly in order to put a halt to the sickness and death rampant amongst black communities. “Everything from the placement of treatment centers in our neighborhoods, the necessity of travel, the quality of care, the access to care, all those things have to be improved,” Fullilove said. “Otherwise, the next wave of the pandemic is really going to do us in.”