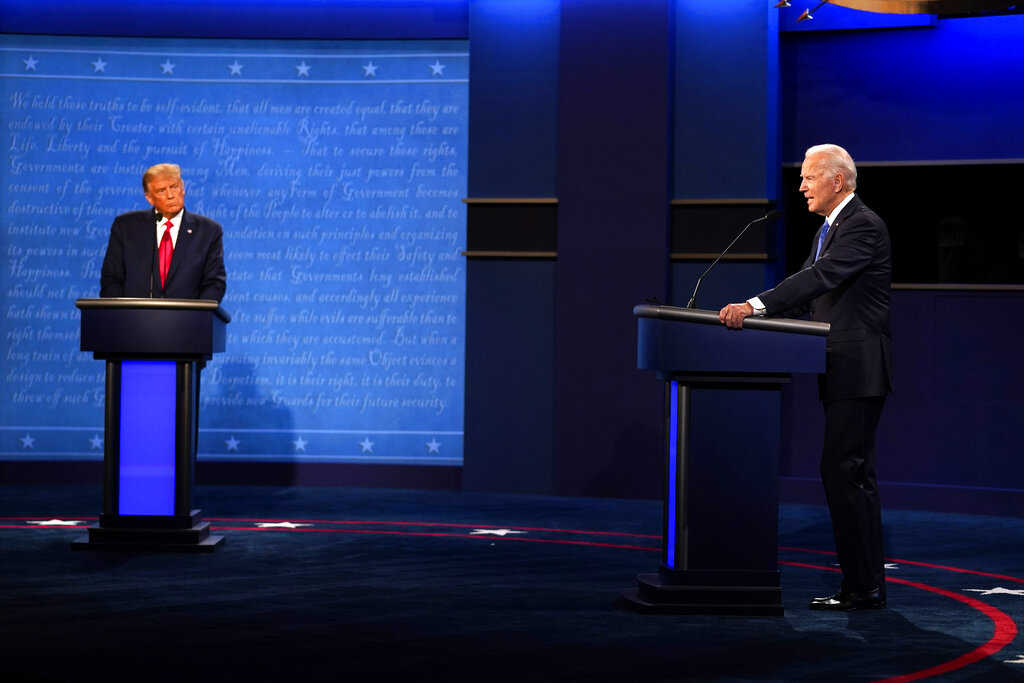

An unruly first presidential debate between President Donald Trump and Democratic nominee Joe Biden raised serious questions about the efficacy of traditional debates, prompting a call for stringent rules to maintain decorum.

It appears it may have worked—at least this time.

Last week’s Thursday night debate, the last ahead of the Presidential election on Tuesday, was a stark contrast to the first, which showcased Trump ignoring agreed-upon ground rules and regularly interrupting former Vice President Biden, who at one point called the sitting president a liar, a clown and then later told him to “shut up.”

“It was an embarrassment,” Bert Neuborne, a law professor at New York University specializing in civil liberties, said in an email of the first debate in late September. “The President turned it into a shouting match, not a debate. It was worse than useless.”

To avoid a repeat, the Commission on Presidential Debate this month imposed a series of changes, including muting each candidate’s microphone during portions “to ensure a more orderly discussion of the issues.” The second presidential debate had been canceled over Trump’s refusal to participate virtually after recently contracting the coronavirus.

“Unlike their first debate last month, the two candidates actually engaged one another,” CNN Editor-at-large Chris Cillizza wrote Friday.

But some are still wondering if debates are useful.

Garrett Schwartz, an internal medicine physician in Northern Nevada, said that he thinks debates are not necessarily for learning about specific policy decisions. Instead, they allow Americans “to get a gauge on” the candidates.

Presidential candidates first debated each other on television in 1960, when John F. Kennedy debated Richard Nixon. But televised debates do not change whom voters will choose, according to a recent Harvard Business School study.

“We do not find any significant impact of TV debates on individual consistency between vote intention and vote choice – or between policy preferences, issue salience, or beliefs on candidates expressed before and after an election,” according to the study.

Still, some voters, like Karyna Colyer, a junior at Stony Brook University, say the debates help display the “likability” of the candidates and are necessary. But she prefers a more “engaging” and “personal” town hall format where citizens from different demographics can directly ask questions.

However, Schwartz and Neuborne, said they favored a more varied debate structure along with town halls.

While many still recognize the value of debates, others like Schwartz, would also like to see more “back and forth” dialogue between candidates and less reliance on the moderator to point out attempts at dodging questions.

Colyer said she wishes moderators would be more forceful about pressing candidates to answer the questions. In addition, she thinks they should focus more on framing questions in a non-biased way.

Neuborne agrees. When asked what he would change about the current debate format, he said he would “significantly strengthen the powers of the moderator.”

But the candidates personalities also still play a major role.

Schwartz credited the lack of “civility and respect” at the first presidential debate to Trump and the divided political climate.

The Commission is hoping the new rules will likely help future debates run more smoothly.

“We are comfortable that these actions strike the right balance, and that they are in the interest of the American people, for whom these debates are held,” according to their statement.