Every sports fan in America wants a team to call their own. All around the country, home teams bring enthusiasm and pride to the cities they represent. Historically, these organizations have only expected one thing in return: a stadium.

Once called “Modern Day Cathedrals”, stadiums are only becoming more elaborate and more expensive. Within the NFL, team owners today are worth anywhere from $1 billion to $13 billion. That’s billion with a B. Still, when deciding who foots the bill for stadium construction, the debate is an ongoing one. Public or private?

With money comes politics, a central aspect of decision-making on a scale this huge. Someone must decide the stadium design and overhead cost. Meanwhile, another person must negotiate with city and county municipalities. Perhaps the most unlucky of the bunch has to pass this information along to taxpayers.

Super Bowl LV champs Tampa Bay Buccaneers provide an interesting case study on the history, successes, and failures of publicly funded stadiums over a 20 year period.

Tampa’s Raymond James Stadium, also known as the “Ray Jay”, cost taxpayers $168.5 million dollars. New owner Malcolm Glazer who had purchased the team three years before didn’t pay a cent, despite initially promising to cover half the cost if fans put down 50,000 deposits on 10-year season ticket commitments. When that didn’t happen, taxpayers paid the price.

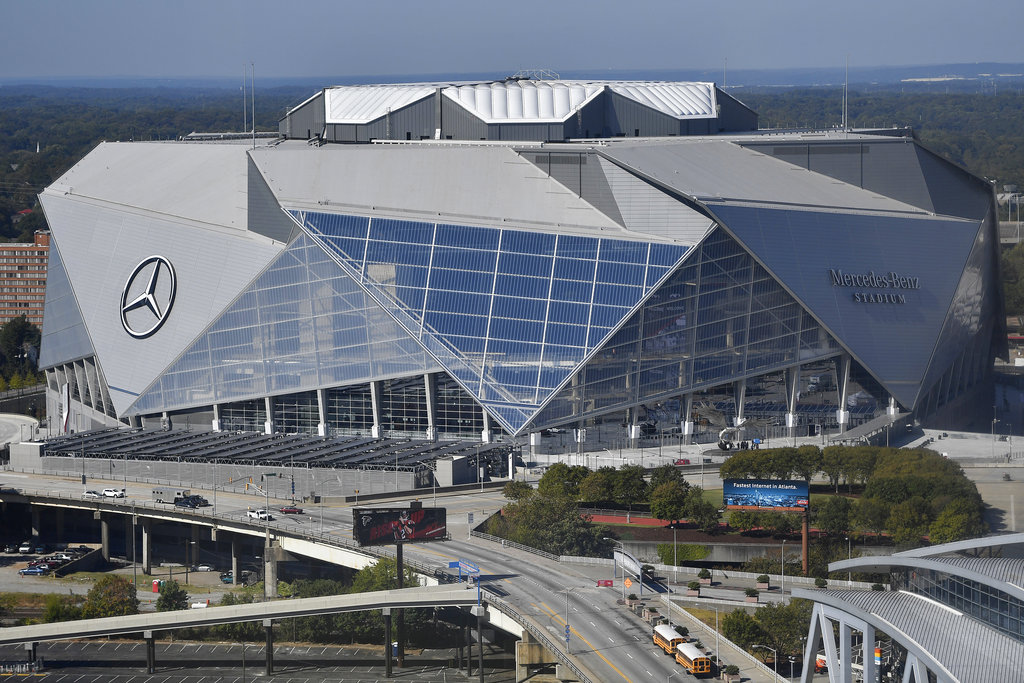

Rich McKay, current President and CEO of the Atlanta Falcons, is believed to be the only current NFL executive who has successfully built two stadiums – the first being the Raymond James Stadium and more recently the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in downtown Atlanta. Nobody understands the politics involved from idea to execution better than McKay.

In Tampa’s case, McKay was responsible for navigating three different entities who all had a say in the stadium’s construction.

“You had to get the county commissioners to approve, you had to get the city council to approve, and you obviously had to get the Tampa Sports Authority to approve,” McKay explained. “So you had three different paths you had to go down, and that made it somewhat tricky.”

While today a $168.5 million dollar stadium seems low-cost compared to McKay’s Atlanta project, which cost $1.6 billion, convincing taxpayers in Tampa to fork out the money was no easy task. One reason for this was the reputation of Glazer, an out-of-towner who had threatened to move the team more than once.

Rick Stroud, a longtime beat writer for the Buccaneers in the Tampa Bay Times, remembers the tension well. When asked about the politics and local negotiations that went into the project, Stroud called them “very contentious for a number of reasons.”

“Chief among them was the fact that the Buccaneers were sold, not to a local ownership group, but to Malcolm Glazer, who came in with a reputation of being sort of known as a corporate raider. He had had discussions about purchasing other pro sports franchises,” Stroud explained. “He was from Rochester. People were aware that he had talked at times with the Baltimore stadium folks who were trying to lure the NFL back there… I think skepticism is probably as close as I could get.”

When it comes to NFL stadiums, some, like the Ray Jay, were funded publicly, while others, like the Gillette Stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, used private money. Some are a mix of the two. But the more public money required, the larger the pitch. And, not every taxpayer cares about football.

“Back then, as now, maybe even more so now, the community had a lot of needs,” Stroud said. “So anytime you were talking about funding a community financed stadium for a multimillionaire, or even billionaire owner, for them to operate their business, that was a tough sell.”

It was an even tougher sell for someone like Glazer who had no prior involvement in the local community. With the lack of an established trust in Glazer, taxpayers questioned how they would know how much of their money was being allocated to the appropriate places. When Judith Grant Long looked at stadium funding trends in 2013, she determined that the average stadium deal cost taxpayers 40% more than the stated public cost – and that number was rising over time.

Still, after months of negotiations, McKay and Glazer found success after proposing the Community Investment Tax, a 30-year half-cent sales tax increase that would pay for various public improvements along with a new stadium for the Buccaneers.

“I think the community investment tax was the saving grace. It was the idea that gave us a chance to unify everybody,” McKay said. “We’re only getting 11% or whatever percent it was of that tax, and the other 90% is going to fire, education, police, and roads and fixing malfunction junction… So the phrase is corny, but it’s true, which is if you can do a transaction where there is a win-win, you have a better chance of having that transaction succeed. And that’s what we were trying to do.”

On September 3, 1996, the ballot measure passed by a margin of 53% to 47%, and the Raymond James Stadium was built. Since then, the stadium has hosted three Super Bowls, four NFL playoffs, one College Football National Championship, and several large-scale concerts.

“The bottom line is that the Bucs made a very, very good deal for themselves. Incredible deal,” Stroud said.

As McKay mentioned, sports teams seeking public funding tend to argue the positive economic impact that a sports franchise has for a city or state and local economy. However, especially as stadiums are becoming more expensive, this idea of the “multiplier” or “substitution” effect has not convinced everyone.

Neil deMause is a journalist and author of Field of Schemes, a site focused on “casting a critical eye on the roughly $2 billion a year in public subsidies that go toward building new pro sports facilities.” To him, and to the majority of sports economists, the proof is just not there.

“At this point, there’s more than 30 years of economic studies showing clearly that the presence or absence of a sports team in a city has no measurable impact on how much money is spent there. The likely explanation is what economists call the ‘substitution effect,’ which simply states that most people have a limited entertainment budget, and if they spend more on sports tickets, they’ll spend less on something else, like eating out or going to movies. On the whole, the economic spending benefits from gaining a sports team are at best a tiny fraction of team owners’ claims,” deMause explained.

While the Buccaneers were able to swing a deal in Tampa that worked in their favor, other local teams haven’t had such luck. In 2018, the Tampa Bay Rays proposed a new stadium that would move them from a failing arena in St. Petersburg to the heart of Tampa’s Ybor City. However, there was one slight difference: it would cost taxpayers over $800 million more than the Raymond James Stadium.

Having the lowest attendance in the MLB five times since 2012, the majority of people agreed the proposed Ybor Stadium would fail – and it did. Now, the Rays are shifting to other options, like a split season between St. Petersburg and Montreal.

(Eric Kilby, via Flickr)

While the Buccaneers have called Tampa home since their first kickoff in 1976, the Rays never seemed to fit into the fabric of Tampa in the same way. As a transplant team playing across the bridge in St. Petersburg, the appetite for taxpayers to invest hundreds of millions in the team simply was not there.

“Almost from the beginning when the Rays were an expansion team given to the Tampa Bay area, there was a lot of rivalry between Tampa and St. Petersburg over who could offer a stadium to Major League Baseball first,” Stroud stated. “That thing they proposed in Ybor, they didn’t know how to finance it from jump street… But the biggest problem was that at no point did the owner of the Rays, Stuart Sternberg, say, ‘This will be my contribution to the cost of the stadium’, he never attached a number to it.”

While the Rays argued their low attendance would be solved by a shiny new home stadium, deMause disagrees.

“If you look at the history of baseball, no new stadium has had a significant impact on attendance over the long term, regardless of the market size of the city it’s in,” deMause said. “You get a honeymoon period of between two and seven years (depending on whether the team is good enough to keep people interested, mostly), and after that attendance drops right back down to around where it was in the old stadium.”

Looking forward, as team owners become richer and stadiums more expensive, stadiums like the Raymond James might be the last of their kind. The newest full-time NFL stadium, SoFi Stadium in Inglewood, California, home of the Los Angeles Rams and the Los Angeles Chargers, was completed in 2020 using $5 billion in private money. The $1.9 billion Allegiant Stadium in Las Vegas, also completed in 2020, was partially funded with $750 million generated by a 0.88 percent hotel occupancy room tax increase. In McKay’s eyes, public taxes like these can still be mutually beneficial.

“Whether it’s in infrastructure, land, zoning, there’s plenty of places that the public can play a part… [Mercedes Benz Stadium] has 54 events that are 40,000 or more people. So forget our 10 games, just look at the other 44 events and realize every one of those has hotels, restaurants, airport, all the benefits. I still understand the public pushback, and there is a big share that the private entity should pay. By the same token, there’s a public benefit,” McKay explained.

“I can sit there all day long and debate the economist as I’ve done, I think I did it on a PBS station in Tampa once where somebody was screaming at me that there was no benefit. I don’t buy that for one inch. I know the benefit. I’ve seen it,” McKay said.

deMause’s stance on the subject likely aligns with that economist that faced McKay.

“If history is any guide, we’re in line for more of the same: Team owners getting more and more creative in finding ways to demand public subsidies while pretending that they’re not,” deMause said. “I keep hoping that this scam will finally run its course, and that maybe I can even stop writing about it eventually, but it seems to be way too central to North American sports leagues’ business model for anyone to let go of it anytime soon.”

For Stroud, the future of stadiums in Tampa likely has less to do with the Rays and more to do with the Buccaneers playing in a stadium that is now 22 years old. Whether that means a new stadium might be in their future, or simply undergo constant renovations, taxpayers will surely have something to say.

“We live in this kind of cocoon where we think sports is so relevant to everyone when it’s not. It’s going to be a close vote and a tough sell. It’s going to require, I think this time around, more of a commitment in actual dollars from the ownership.”