Russian New York University faculty and students on Friday expressed opposition and disappointment over President Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine.

Speaking after a panel discussion hosted by the Jordan Center for the Advanced Study of Russia, Anastasia Vlasova, a freshman student from Moscow with friends and relatives in Ukraine, said she’s “incredibly disappointed in the Russian regime for inflicting death upon innocent lives and sabotaging its own people that don’t even support the invasion of Ukraine.”

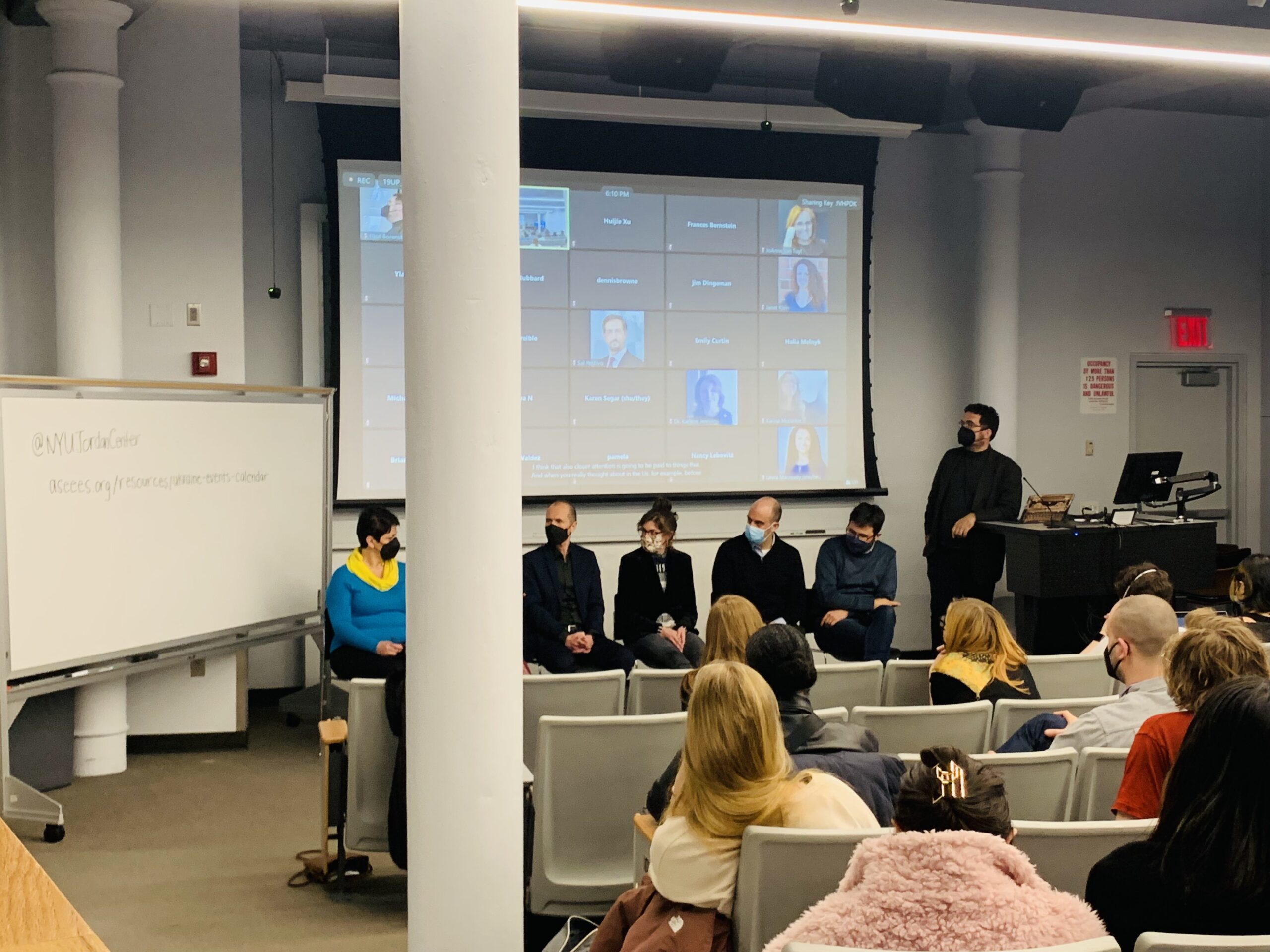

She joined other students in listening to NYU faculty dissect the war, Russian perceptions over the invasion, and whether Putin misread Ukraine’s decision to defend its 30-year independence under President Volodymyr Zelensky’s leadership.

Joshua Tucker, the director of the Jordan Center and a professor of Russian and Slavic Studies, explained there are a number of reasons why Putin invaded, including security concerns, his desire to hold onto Russia’s power, and his legacy.

Tucker said the war on Ukraine is important to Putin because he sees the country’s break from the Soviet Union as the “worst tragedy of the 21st century” and restoration of the territory would help to rebuild his legacy.

Anne O’ Donell, an associate professor of History of Russian & Slavic Studies, added that, to Putin, Ukraine’s independence was foolishly given by Russian officials, and now Russia wants to take it back. But the reality is that when Ukraine joined the Soviet Union in 1922 as an independent republic, it envisioned a different political future with Kyiv as a political and cultural center, she added. Ukraine finally won its independence in 1991.

Margarita Boyarskaya, a Ph.D. student at NYU and a Moscow State University graduate, agreed, adding: “The Putin regime is attempting to instill the idea that there is no reason Ukraine should have ever become sovereign and independent territorially.”

Before the wave of civil unrest in Ukraine in 2013, a majority of Russian people viewed Ukrainians as cultural brothers and sisters, but that sentiment has since shifted following Russian state propaganda efforts to disrupt the harmony between both sides.

Russian began to introduce “a brand new idea of disunity and hostility between Ukrainian and Russian peoples,” Boyarskaya said.

At the event, some Russian faculty members, like Natalia Levina, a professor at NYU Stern’s School of Business, also shared stories of their Ukrainian relatives suffering with family members living under the threat of daily bombings.

Elsewhere on campus, Russian students have been finding it difficult to separate from the barrage of news and anti-Russian sentiment rapidly spreading through the world.

Polina Tyurikova, a NYU sophomore from Moscow who has family and close friends in Russia, said it’s been difficult to escape the constant coverage of the military invasion.

“I never knew that I would ever be in this kind of position,” Tyurikova said. “And the fact that there’s so much attention — I feel like everyone’s looking at Russia. I feel like I have to speak even though I always abstain from politics.”

Tyurikova has been active on social media sharing articles and resources about the invasion, as well as her personal sentiments as a Russian who’s appalled by Putin’s actions.

For others, the spread of anti-Russian sentiment has led to uncomfortable interactions in public.

NYU Freshman Yana Bulavchenko said she “was walking in Washington Square Park on the phone with [her] grandmother speaking Russian” when her grandmother interrupted her to ask, “’Are you speaking Russian in public?’”

Bulavchenko told her, “Yes.”

“And [my grandmother] says, ‘You shouldn’t do that’ – that broke my heart.”

Trystin Aiko Kahanano’eau Lopes and Farheen Khan contributed to this report.