Yevhen Trachuk left Kyiv on Feb. 28. After a week of hiding in metro stations at night to avoid bombs and spending his days drinking and smoking in his Kyiv apartment, Trachuk got on a train and went west, to the Ukrainian city of Ivano-Frankivsk.

Trachuk is a 25-year-old LGBTQ rights activist and works with the LGBTQ rights organization Kyiv Pride to promote LGBTQ visibility throughout Ukraine. Now, his mission is a bit different: help members of Kyiv Pride and the LGBTQ community relocate to western Ukraine or abroad, and provide them with housing, medicine and food.

On Feb. 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation” against Ukraine. In a pre-dawn address, he called for the “denazification” and demilitarization of Ukraine. Putin also referenced “traditional values” in his speech, which is widely recognized as code for anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, while attacking Western ideology.

“They sought to destroy our traditional values and force on us their false values that would erode us, our people from within, the attitudes they have been aggressively imposing on their countries, attitudes that are directly leading to degradation and degeneration, because they are contrary to human nature,” Putin said.

Since then, Russia has sent approximately 150,000 troops into Ukraine, and more than 400 civilians and thousands of Ukrainian troops have been killed.

Now LGBTQ activists in Ukraine and the U.S. worry that this invasion could have outsized consequences for LGBTQ Ukrainians.

“We have seen first hand how geopolitical conflicts disproportionately affect marginalized communities including LGBTQI+ people,” Rainbow Railroad, an organization that helps LGBTQ people facing persecution, said in a statement. “We are concerned about the impact this conflict will have on the LGBTQI+ community in Ukraine.”

Ukraine’s LGBTQ population is explicitly referenced in a letter to the United Nations penned by members of international organizations, including Bathsheba Crocker, the U.S. ambassador to the UN. The letter claimed the U.S. has “credible information” about a Russian “kill list” of potential targets for the invasion of Ukraine. The letter, first reported by The Washington Post, claims Russia will likely target Russian and Belarusian dissidents, journalists, anti-corruption activists, religious and ethnic minorities, and LGBTQ people for killings, kidnappings, detentions and torture.

“It’s pretty basic for Russia I think [to] just hunt people they don’t like,” Trachuk said. “If Russia takes control of Ukraine it’s bad for all and for gay people also, because still they don’t like gays like. Gays in Chechnya get stopped and put to prison.”

This isn’t the first time Trachuk has been forced to leave his home. He grew up in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region, which has been partially controlled by Russian-backed separatists since 2014. Trachuk is nonbinary and remembers being scared when the Russian occupation of Donbas began because he thought Russia would bring anti-LGBTQ views to the region.

Nevertheless, in 2019, Trachuk created an LGBTQ rights organization in his hometown. Just a year later, he fled to Kyiv because he had become too recognizable.

“It was kind of impossible for me to stay because people saw me on the streets and they were kind of angry.” Trachuk said.

In 2014, when Russia invaded Crimea, part of their strategy included inundating Ukrainians with anti-LGBTQ propaganda. U.S.-based Ukrainian LGBTQ rights activist Bogdan Globa said this has made the situation in Ukraine worse for LGBTQ people.

“Russia, they put in all of this anti-LGBT narrative, traditional family values, and all of this stuff,” Globa said of the propaganda. “Unfortunately, it’s working.”

After the occupation of Crimea, a Russian anti-gay propaganda law went into effect in the region, which made it illegal to distribute material about the LGBTQ community to minors. The head of Crimea’s regional government, Sergei Aksyonov, said that if the LGBTQ community ever tried to stage a parade or public event, they would be met by police and paramilitary forces.

A 2016 report by the Anti-Discrimination Center Memorial and the Center for Civil Liberties found that, since 2014, members of the LGBTQ community in Crimea and the Russian-backed separatist-controlled Eastern Ukrainian cities of Luhansk and Donetsk had been subject to constant discrimination and persecution. The report also documented instances of torture and beatings of LGBTQ people in Crimea. It is estimated that thousands of Ukrainians have left Crimea for mainland Ukraine since the occupation, many of them minorities or LGBTQ individuals.

After Russian-backed separatists took control of Luhansk and Donetsk, the constitution of the Donetsk People’s Republic banned any “perverted union between people of the same sex.” The Luhansk People’s Republic introduced a criminal penalty for homosexuality.

“They criminalized LGBT there. There even were rumors about they killed several LGBT people,” Globa said. “So if Russia will move forward and grab even more territory… LGBT are first targets.”

LGBTQ refugees or internally displaced people face risks others don’t, and can face discrimination while trying to get humanitarian aid or resettle.

More than one million refugees have already fled Ukraine since Russia’s invasion began, according to the UN. Many of them are seeking safety in the neighboring countries of Hungary and Poland, which have their own homophobic policies. And, even if they wanted to, not everyone can flee Ukraine. Ukraine banned all male citizens ages 18 to 60 from leaving the country, leaving some LGBTQ individuals with no option but to stay.

Prior to Russia’s invasion, Ukraine wasn’t a paradise for LGBTQ people. According to a 2021 survey, 47 percent of Ukrainians have a negative view of the LGBTQ community, and Ukrainian law does not recognize homophobia and transphobia as motives for hate crimes.

But the country is a regional leader on LGBTQ rights and has a visible network of LGBTQ rights organizations. The fragile progress the country has made on LGBTQ rights is put at risk by Russia’s invasion.

Bogdan Globa was born in Poltava, Ukraine in 1988. He came out as gay when he was fifteen at a time when Ukrainians didn’t have access to the internet. His parents first tried to send him to a psychiatric clinic, but the clinic told his parents that being gay wasn’t considered an illness anymore. They began beating him instead.

Later Globa moved to Kyiv, and became a human rights advocate, creating HIV testing clinics and an LGBT parents organization, and becoming the first openly gay man to speak in Ukrainian Parliament. In 2016, Globa claimed political asylum and moved to the U.S. after receiving death threats for his activism. Now he’s the president of QUA, an association for LGBTQ Ukrainians in the U.S.

Globa says the situation for LGBTQ people in Ukraine has improved drastically in the last few years. As Ukraine attempted to get access to visa-free travel with the EU, it adopted a more tolerant legal view towards the LGBTQ community.

“LGBT much more visible now,” Globa said. “It’s much more information. At same time, it’s still a lot of stigma.”

In 2015, the Ukrainian Parliament removed a Russian-inspired bill called “On the Prohibition of Propaganda of Homosexuality Aimed at Children” from its agenda after it was criticized by the European Union. More anti-gay propaganda bills were introduced in 2018 and 2020, but have not passed.

In the past few years, thousands of people have marched in Ukrainian pride parades.

“Even though we don’t have … laws that I can marry someone I love here … the society in general became more tolerant,” Trachuk said.

But opposition remains, encouraged by Russia. Russia has used homophobia as a state strategy for years, according to Nikita Sleptcov, author of the paper Political Homophobia as a State Strategy in Russia. He says Putin uses the LGBTQ community to demonize the West and as a scapegoat to distract from domestic issues.

If Russia occupies Ukrainian territory, “anti-LGBT propaganda and political homophobia will definitely be a strategy. Absolutely,” Sleptcov said. “This is anti-Christian they would say, this is anti-anything, they would say it’s a threat to our societies.”

Lyosha Gorshkov has personal experience with the effect that Putin’s rhetoric can have. Gorshkov is nonbinary, and grew up in a rural town in Russia’s western Perm region in the 90s. Gorshkov got a PhD in minorities with a focus on LGBTQ studies and began teaching queer studies. Soon, Russian security agents began following Gorshkov. Then things got worse.

In 2012, Russia passed the Dima Yakovlev Law and the “foreign agent” law, which suspended the activity of politically active non-profit organizations that receive money from American citizens or organizations and required those non-profits to label their content as the work of a foreign agent.

In 2013, Russia passed an anti-gay propaganda law that made it illegal to distribute material about the LGBTQ community to children, and led to an increase in anti-gay violence. The stated purpose of the law was to protect children from “information promoting the denial of traditional family values.”

Gorshkov says the anti-gay propaganda law allowed the security agents to come out of the shadows.

“They started proactively approaching and trying to recruit me to report on people who expressed different opinions or who had different identities,” Gorshkov said. “An article came out about myself and my colleague, calling for us to be fired for propaganda of sodomy. And things evolved and physical violence occurred multiple times.”

Gorshkov started moving from one apartment to another, staying in secure locations. He fled to the U.S. in 2014, and is now the director of LGBTQ+ Initiatives at Colgate University and the co-president of Russian-speaking LGBTQ organization Rusa LGBT.

Gorshkov says there’s no question that Putin would enact homophobic laws in Ukraine if he took control.

“The whole package will be implemented, will be just imported without any hesitation. If not worse,” Gorshkov said. “Because Ukraine has chosen the way to be free and leaning towards Western values. And Putin did not like that.”

In 2020, Putin expanded the definition of “foreign agent” to include ordinary citizens who receive money from abroad and are involved in “political activity.” Failing to register as a foreign agent can lead to fines and jail time.

In a letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken, the Congressional LGBTQ+ Equality and Ukraine Caucuses said “increased Russian government influence on the lives of Ukrainians is likely to be incredibly harmful to the rights of LGBTQ people in Ukraine.”

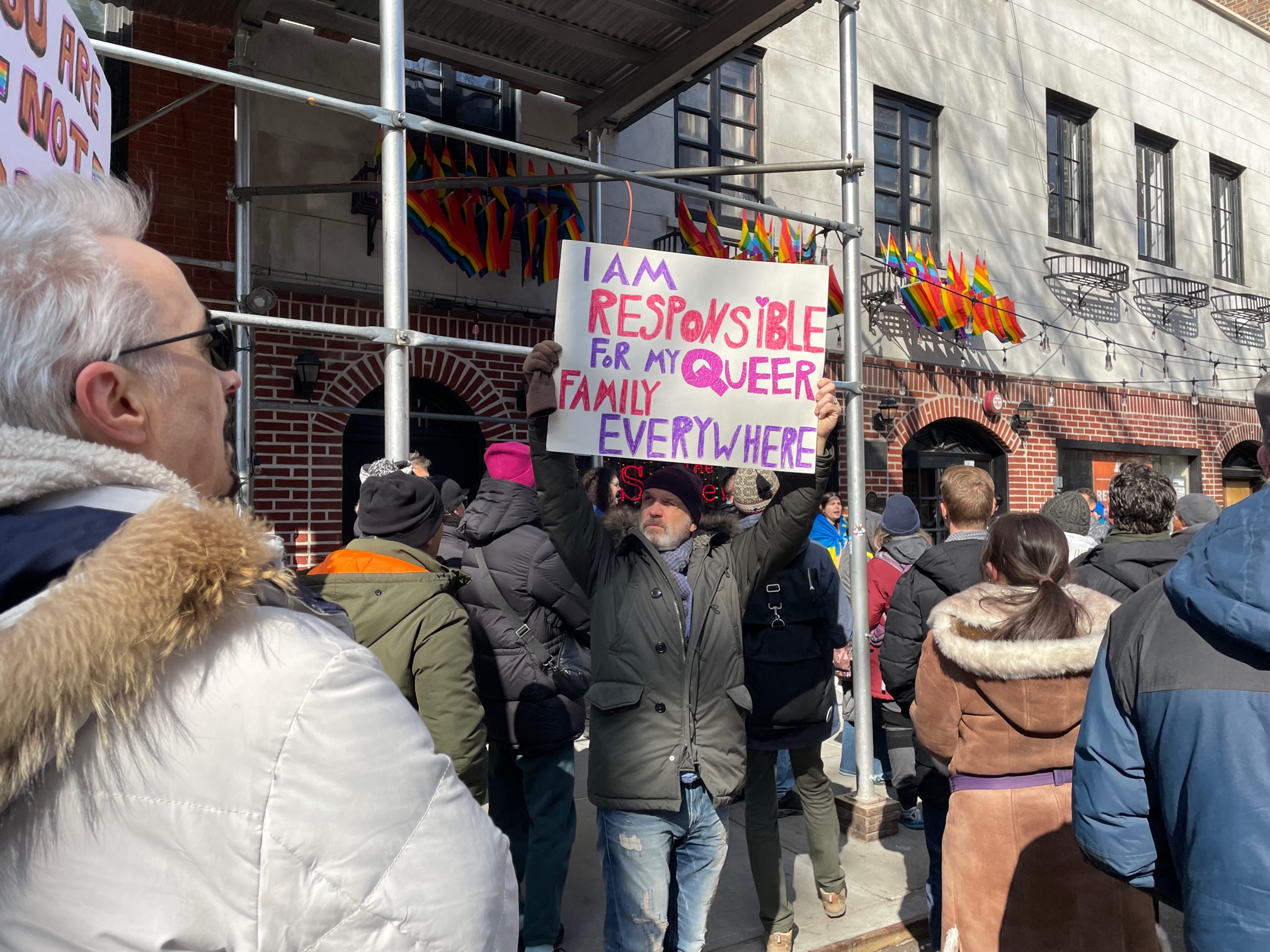

Globa wants LGBTQ organizations in America to be more vocal in their support of Ukraine, and to coordinate with and give money to Ukrainian LGBTQ organizations.

“For LGBT, I think, what we should do more, we should have a plan,” said Globa. “I don’t think they have a real plan for now. And I think it’s a problem because I believe LGBT will be one of the first target.”

But all the activists agreed that this conflict goes beyond the LGBTQ community. Trachuk said for the first time in his life he is no longer fighting just for the LGBTQ community or himself—he is fighting for all of Ukraine and all Ukrainians.

“I don’t want to live in Russia because I was born in a free Ukraine, independent Ukraine,” said Trachuk. “We have to fight for our freedom… it doesn’t matter who you are.”