“Not everybody likes this joke” Alexander Martynov, the 48-year-old owner of Prague’s Ukrainian restaurant The Borsch says, his smile widening. “I’m saying they lose their borscht virginity here.”

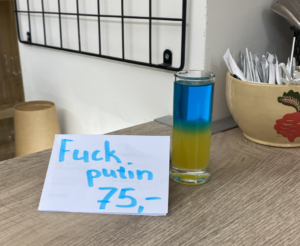

If you happen to wander into The Borsch, located in the Vinohrady area of Prague, you’ll find a colorful display of culture and cuisine. Printed pillows hang from the walls adorned with Petrykivka, an embroidered, traditional Ukrainian style of design. Customers sit on colorful cushions and chat between bites of varenyky, a Ukrainian dumpling. They speak in an array of languages, some of them sipping on the restaurant’s “Fuck Putin” cocktail, a blue and yellow drink that costs the equivalent of around $3.

Alexander Martynov leans against a wall behind the bar, having just hung a Ukrainian flag on the storefront to prepare for the restaurant’s 11 a.m. opening. He dishes out steaming portions of borscht and takes orders from customers in English, Ukrainian and Czech, the last of which he has been taking weekly lessons to learn. Martynov sports a clean-shaven head and a navy hoodie with jeans as he discusses business with his wife and co-owner Natalia Bass.

His restaurant has seen an influx of Ukrainian customers since Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24. Across the world, from Prague to New York, consumers have put their money toward Ukrainian establishments as a show of support.

Despite the recent increase in patronage, The Borsch has always had a unique status as an international restaurant in the Czech Republic, a country often criticized for a lack of diverse cuisine. Now, Martynov is tasked with feeding a new demographic interested in supporting Ukrainian businesses in the ongoing war.

Although Prague is a major European city, its home country of the Czech Republic is often known for a deficit of healthy and tasty food. Celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain once called the country “the land that vegetables forgot,” and 97% of Czechs have called for better quality food, according to Radio Prague, a Czech news site.

Martynov’s customers are critical of Czech food, too — he said that many of his Ukrainian patrons in particular were relieved when they found his restaurant.

The Czech Republic spent 41 years under communist rule, during which chefs were issued just one cookbook of allowed recipes, leaving sparse opportunities for culinary innovation. Czechs have embraced international restaurants since the fall of communism in 1989, but introducing new cuisines anywhere does not happen quickly.

“On one hand, we are quite exotic, because people usually don’t know that stuff and there are not that many Ukrainian places compared to even Mexican,” Martynov said.

The Borsch, which opened its doors last year, is the only exclusively Ukrainian restaurant in Prague. Yet in 2019, Ukrainians made up the highest percentage of foreigners in this city at a little over 25%, according to the Czech Statistical Office.

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, the demographic of The Borsch’s customers was typically one-third Ukrainians, one-third individuals from formerly-soviet-controlled countries and one-third Czechs, Martynov said. Now, he serves mostly Ukrainian customers — many of whom have come to Prague seeking safety amid the war.

The Borsch executed Martynov’s original vision: to bring Ukrainian food to Prague and to “introduce Ukrainian food to foreigners, expats who live here.” He recalled one customer who, unable to pronounce the word borscht, simply pointed at a picture of the soup and told him, “I want this stuff.”

Martynov is new to the restaurant business. He came to Prague five years ago when he was offered a job in the tech industry. His idea to start a Ukrainian restaurant began as a recurring joke between him and his wife, and it came to fruition as a result of two things: an Instagram post in which the Michelin Food Guide called borscht a traditional Russian dish and later, a famous Ukrainian chef who campaigned UNESCO to recognize borscht as a Ukrainian dish.

It was then, Marynov said, that his wife “succumbed to the idea.” Now, Bass manages the restaurant full time, working with Martynov as he splits his time with his tech job.

Bass, who is also from Ukraine, beams when she describes the reaction of their customers, noting, “at last they feel something native.”

Martynov said the rest of his family is still in Ukraine, including his mother in-law, sister in-law, and niece. They live in the central part of the country, which is free from active warfare aside from bombings “time to time,” which Martynov said “people get used to it.”

Ukrainian immigrants and Prague citizens don’t just show their support for the country at The Borsch. Across the city, Russian delis have been changing their names or selling Ukrainian ice cream, and local businesses have dedicated some of their funds to nonprofits and humanitarian organizations, according to a representative of the culinary website Prague Food Guide.

Martynov hasn’t changed his business model, though. The only difference he has been considering since the influx of new customers is adding a menu in Ukrainian as a response to several customer requests.

Both Bass and Martynov check the restaurant’s Google reviews, and take pride in the fact that they can make “a small place of Prague feel like home,” as Bass said.