On Carmine Street in Greenwich Village, inside Temperance Wine Bar, sits two bookshelves, lined with various rare and niche books. They aren’t for decoration, nor are they sold by the restaurant. Instead, they belong to Jim Drougas’ Unoppressive Non-Imperialist Bookstore.

After 31 years of business, the landlords of Drougas’ store increased the rent to a rate that he could no longer afford, forcing him to close up shop. Or at least that was until the wine bar next door offered its space to continue his legacy.

When the restaurant owners proposed to their staff opening up space for the bookstore “they jumped out of their chairs and said, yes, you have to do this,” Drougas tells me. And despite the downsizing, business has still been good. “Even when things are pretty desolate here, in general, as they have for long years, somehow we seem to thrive,” where he’s been able to sell out the right copy of books within a matter of weeks.

As Drougas describes, the community surrounding his store seems to be a strong one, and it’s one of the reasons why he has continued to sell books since the 70’s. “It’s not all together meaningful making a large income. It pays some bills. It’s more important, the other aspect, finding, meeting people, old friends and new friends,” the bookselling veteran says. “There’s really all this love that just comes gushing out all day long. That’s edifying.”

In recent years, there has been a rise in the number of independent bookstores both in New York City and across the country. More than 300 stores have opened up, according to the American Bookseller Association (ABA), a not-for-profit trade organization that supports independent bookstores. These include “education, information dissemination, business services, programming, technology, and advocacy,” as stated on their website. And in the next few years, they expect another 300 stores to open, Allison Hill, CEO of the Association, tells me.

But it hasn’t always been the case for the industry. When the country’s largest book chain, Barnes & Noble and Borders, expanded the number of stores in the early 90’s, followed by the Amazon revolution in online retail space for bookselling, releasing the Kindle in 2007, the independent bookstore industry suffered. Between 1991 and 2009, the ABA membership decreased by more than 70%, highlighting the effects that the various changes to book consumption had on the industry.

“When I started selling books in 2003, most independent bookstores had closed. It was the era of bookstore chains,” says Corey Eastwood, co-owner of Codex Bookstore in the East Village. However, with the financial crisis in 2009, chain bookstores were forced to downsize or close down completely. “What was left was space for independent bookstores, which offered an experience Amazon couldn’t provide.” And over the next decade, the number of independent bookstores across the country would rise by 30%, according to data from the ABA.

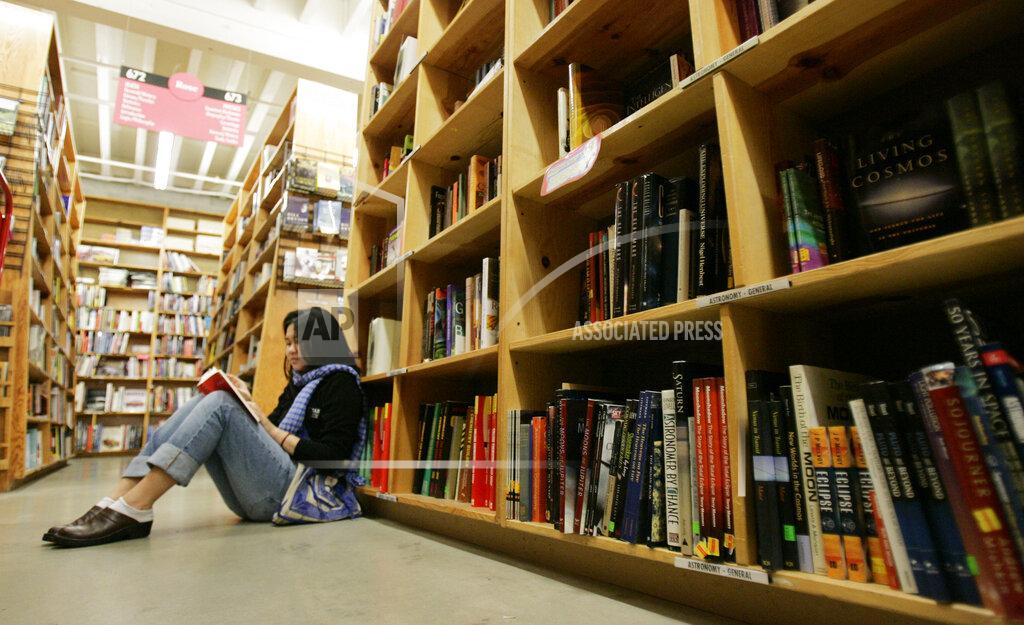

In the narrow but long interior of Codex, the walls are stacked from floor to ceiling with books along deep shelves that stretch all the way to the back of the shop. On the shelves are a mix of old and new books that focus on literary fiction and art. “It’s the actual physical, personal experience of going to used bookstores that can’t be paralleled online,” Eastwood says. It’s where he’s met some of his best friends, the store owner tells me. “I’m having a wedding in Mexico next year and I could point to you like, oh, customer, customer, customer.”

“Yeah, I really like coming to bookstores like these ’cause the prices are cheaper than standard retailers,” Wyatt Albert, a NYU student, says as he browses the used books section outside of Codex’s store. “It’s also just cool getting to find books that you wouldn’t normally find at a retailer like Barnes and Noble or something.”

But beyond the physical space, what an independent bookstore offers to its community is also important. Karma, a bookstore in the East Village that’s been open for five years, carries books that focus on art and artists, like the French painter Henni Alftan or New York-based poet Eileen Myles. “It’s a pretty niche market, so people always come seek us out,” the store’s director Matthew Shuster tells me.

The store’s interior is largely minimalistic. The walls are painted a soft white, where various pieces of paintings and drawings are displayed. And although there aren’t as many books on display compared to Codex, the ones that are are neatly displayed on top of shelves units for their customers to peruse.

The store works to serve both the people in the neighborhood and artists, but also larger institutions. “We try to have a little something for everybody,” Shuster tells me. “But we also have a lot of exceptional things. Like rare books for universities, libraries and museums.”

Stores like Karma, Codex and Unoppressive are important not only because they fulfill niche needs within the community but also because of their economic contributions to the local area. Nearly 30% of the revenue earned by independent bookstores immediately goes back to the local economy, compared to the 5.8% when shopping on Amazon, according to a study done by the ABA and Civic Economic.

But their contributions are more than economical. “They support and center diverse and new voices, champion authors, promote literacy, nurture young readers, and connect books with readers,” Hill tells me.

And with social isolation becoming an increasingly real problem today, perhaps going out to your local Village bookstore might offer some relief, Eastwood proposes. “With a physical space such as this one, you don’t have to buy anything. You can browse, you can talk to other people. It’s important. It’s socially important.”