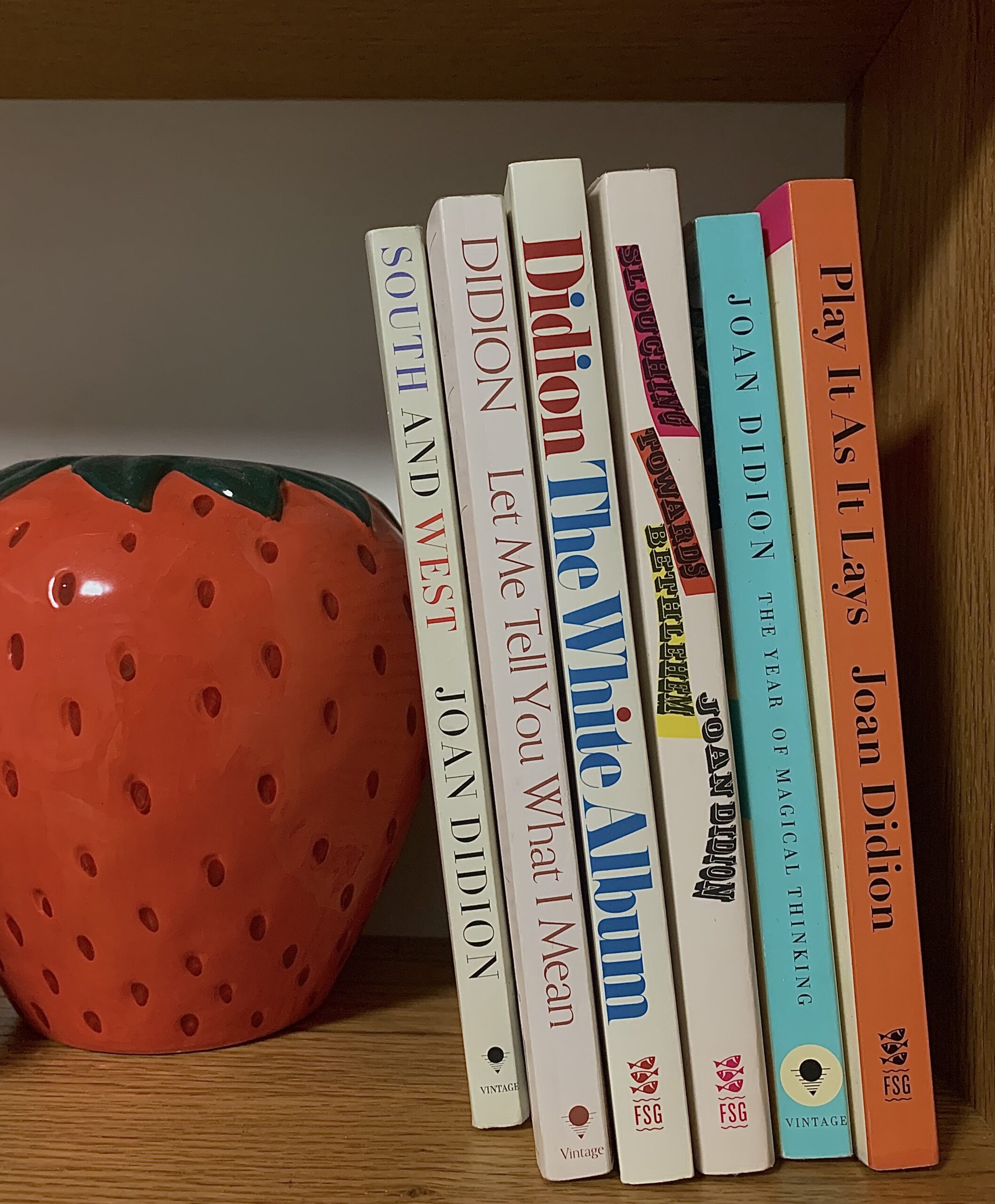

I own more books by Joan Didion than I can count. Some are in my dorm room, piled on my window sill overlooking East Tenth Street. Some are on my IKEA bookshelf at my family home in the suburbs of New York. It’s as if these books are children living in a split custody situation. They shuttle back and forth between houses constantly.

Perhaps I don’t want to count them because that would quantify my love for their author. Her importance in my life should not be diminished to a number. Any number would be too small and there is more to this obsession than just my collection of books.

Her wisdom surrounds me in my daily life. There is a portrait of her above my desk— clad in a floral blouse with a cigarette balancing between her fingers, her dark eyes stare at me as I write. My computer background is a black-and-white photograph of her smoking up against a Stingray car. My laptop has a sticker on its cover reminding me of why I write, in her words: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear”.

Each time the New Yorker publishes an article about her, I receive a link from my best friend, both grandparents, and my mother. Each time one of those people reads a book by her, they notify me. In fact, this New Year’s Eve, as my grandfather and I sat side by side on the couch, we realized that we were both reading “Slouching Towards Bethlehem.”

I decorate my life with her face and her words because I want to be her. The more I see her, the more inspired I feel.

***

It was at my local bookstore, Anderson’s Bookshop in Larchmont, New York, that I first picked up a Joan Didion book. I was interning for the business. As I organized the Essays shelf, my eyes glazed over the name Didion. It was printed down the spine of a light pink book. I pulled it off of the shelf and studied its cover. I saw the words “Let Me Tell You What I Mean” next to a photo of Didion’s face— the same one that now hangs above my desk.

I walked up to the owner, Paulene, at the store’s counter and told her I was going to buy it.

“Just take it. And don’t tell Jenny,” she whispered to me. Jenny did the financials. I took it home.

I was recovering from COVID-19 at this time and most of my life was spent on the couch reading. I averaged two books a day. Needless to say, I finished my first Didion within a few hours.

I had never encountered such magnificent prose. I was electrified by her style when reading a description of Robert Mapplethorpe’s subjects in the essay “Some Women:”

Most were New York women, with the familiar New York edge. Most were conventionally “pretty,” even “beautiful,” or rendered so not only by the artifices of light and makeup but by the way they presented themselves to the camera: They were professional women, performers before the camera. They were women who knew how to make their way in the world.

I was blown away by this essay, particularly because I had always admired New York women. I had always wanted to be one— hence my application to nearly every New York City university. I never could explain what it was about these women that drew me to them. Suddenly, I read Didion, and I could explain it. Her writing was magical to me.

In the preface to Los Angeles Notebook by Didion in “The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism,” Ben Yagoda writes “One thing— maybe the only thing— Joan Didion and Frank Sinatra have in common is The Voice: you could never hear a phrase of Sinatra’s or read a line of Didion’s and think it was the creation of anybody else.”

I was enamored by this voice of hers and I needed to have a voice this strong.

***

Before I had even read “The White Album,” one of her most famous books, I lived my life by perhaps its most well-known excerpt: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” I have always written stories. True and made up.I have always been consumed by words, by books, by pen and paper.

My first notebook was bubblegum pink and marbled and it was filled with a horribly written novel by my five-year-old self. I never took my love for words too seriously. Everyone reads; writing was just a self-mandated bedtime activity.

Didion was the first writer who showed me that I could do this for the rest of my life. I could tell stories seriously.

These days, I write in a “Mon Carnet De Poche” notebook. Its rough pages are full of attempts to emulate beautiful prose in my stories about artists and women and reproductive rights. I want to make just a fraction of the difference that Didion made in the world with her literary journalism.

Not only will I tell myself stories in order to live, but these stories will be the things that make me a living. And I will do it in her honor.