When Ava Chin was growing up in Flushing, Queens, her maternal grandfather told her stories of their ancestors who worked on the first Transcontinental Railroad. Then, in sixth grade as her teacher discussed the topic in class, Chin opened up her textbook on American History only to realize there were no Chinese faces in any of the pictures. It was one of her first experiences with Asian American erasure in the country’s history.

“Not seeing us represented … made me really want to tell our stories, and add our stories to the larger American story,” says Chin, who teaches Creative Nonfiction and Journalism at City College and the College of Staten Island.

Primarily raised by her maternal grandparents, Chin grew up not really knowing her own family story. Her mom worked as a school teacher, and her father wasn’t in her life until her mid 20s, when she finally had the courage to meet him for the first time.

It was then that her journey to rediscovering her family history truly began. It led her to the apartment building on Mott Street in New York City, where her father and other family members grew up, including her maternal grandparents. She would eventually travel the world to track down her family’s story.

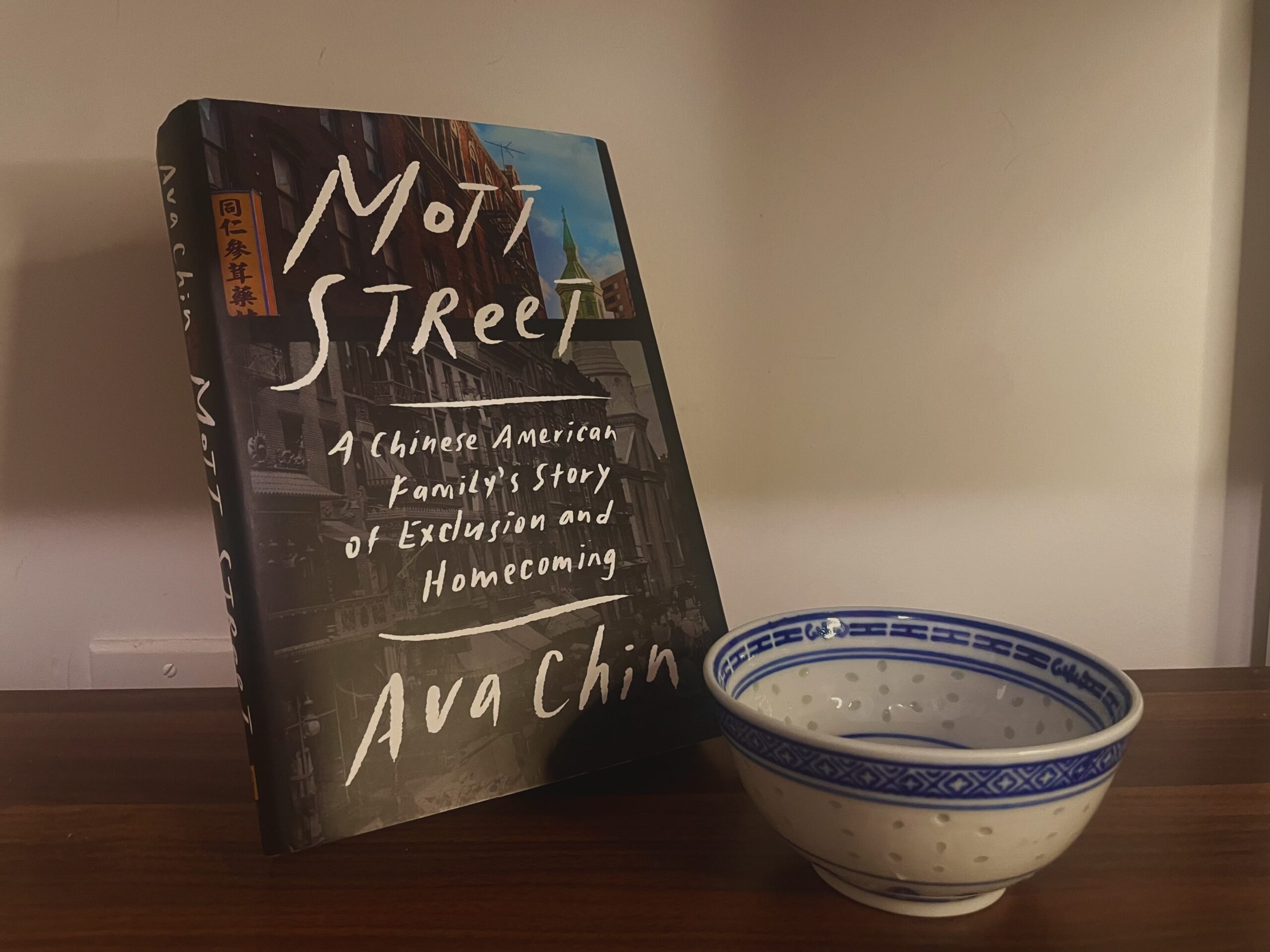

Now, the fifth generation Chinese-American New Yorker is finally ready to add her family’s story into the American narrative. “Mott Street,” her new book, has been earning rave reviews from The New York Times (“sensitive, ambitious, well-reported”), San Francisco Chronicle (“an important read for those interested in learning about the origins of some of today’s most hard-lined immigration policy proposals in America”), Los Angeles Review of Books (“magic”) and Washington Post (“evocative”).

Chronicling nearly 150 years of her family’s story, Chin describes her book as delving into the effect that the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 had on four generations of her family, right in the heart of New York’s Chinatown.

“It started off with my journey, trying to understand my family … I uncovered a wealth of information, something much larger than just our single family.”

The Chinese Exclusion Act was first signed into effect by President Chester A. Arthur, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. It was the first and only law to exclude a specific national group from immigrating into the country, and was not only renewed in 1892, but made permanent in 1902. It would be over 40 years before it was repealed in 1943.

For decades, Chinese immigrants like Chin’s ancestors were subjected to prejudice and discrimination. Her six-month-pregnant grandmother was detained for two months in an immigration facility, which was more like a prison than a waiting center. Her great-great grandfather was driven from his home. A great-aunt, who was white, had her American citizenship revoked for being married to a Chinese man.

“I really want folks to know more of our stories, and I want them to understand the ways in which things happened in the 19th century,” Chin explains. “It was very popular in the 19th century to be anti-Chinese.”

“And that sentiment, particularly out on the West Coast, that anti-Chinese sentiment sunk its teeth into our legal code. And that set a tone and set us on a path in this country to see all Asians as forever foreign and suspicious,” says Chin, from her writing studio on Mott Street.

This idea of seeing Asian Americans as outsiders was revived again during the COVID-19 pandemic, when it was widely believed that the virus came from China. Anti-Asian hate crimes reportedly increased by 124% in 2020, and an over 300% increase in hate crimes in New York City.

In response, Chin helped to co-found a group called Sisters in Self Defense, offering free self-defense classes in Columbus Park for Asian Americans, primarily targeted to women, the elderly and the LGBTQ community. “It was easy going working with her,” says Sokie Lee, one of the instructors who helped to teach the class. “She’s definitely organized, and I appreciate that and the meetings were well run.” Thus, it was understandably upsetting for Chin to hear that one of the participants in her workshop was attacked on Mulberry Street in Chinatown.

Chin was devastated to hear that someone from the class had been attacked in Chinatown. “When I saw the video of what happened, there was no way she could have protected herself,” says Chin, who has a Ph.D. from University of Southern California and an M.A from the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins. “And I just knew as I was working on the book that the stories were becoming more and more relevant and that spurred me to finish it.”

Having been a fellow at the New York Public Library Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers, as well as the New York Foundation for the Arts, Chin was well prepared for the research component of uncovering her family history.

“It was easy working with her,” says Sokie Lee, one of the instructors. “She’s definitely organized, and I appreciate that and the meetings were well run.”

The records for Chin’s family, both oral and documented, were scattered across the world in China and Hong Kong, as well as on America’s east and west coasts. It took countless interviews, with family members, friends of family, and even the people that lived on Mott Street. “You know, it was both long and sometimes painful, but ultimately rewarding,” Chin says, looking back.

“Mott Street” is more than just a compilation of genealogy records, documents and oral history. Chin narrates the book, adding her own ideas on how undocumented scenes likely to play out.

With the numerous omissions and errors in American history, especially relating to Asian Americans, Chin felt there had been stories that were never written about or really brought together. “The official documents were filled with a kind of fiction because the immigration laws were so restrictive that people made up stories to circumnavigate the laws,” Chin explains. “I realized I needed to figure out what [those stories that my family members told me] were based on.”

Chin wants to see more stories than just the one about her family. “I think as Asians, we have a tendency to self-censor and to maybe be a little hesitant, really self-critical,” Chin says. “And I think now is a really critical time to get our stories out there as much as possible.”