Alex Miller recognizes that he has beat the odds.

“Statistics aren’t on any of our sides,” said the 37-year-old U.S. Navy veteran turned New York writer. “Most Black people sink to the bottom. I don’t know how many actually make it out.”

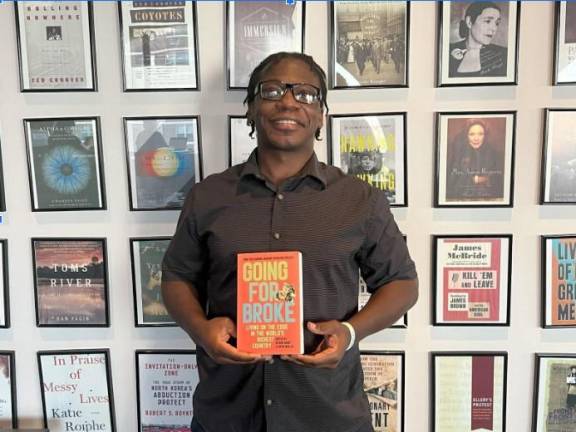

For most of his life, Miller fought to escape the destructive effects of poverty, childhood abuse, and later alcoholism to numb his pain. Nevertheless, today he is an accomplished writer published in The New York Times, Washington Post, and Esquire. In his essay, “37,000 U.S. Veterans Are Homeless – I Was One of Them,” featured in the book, “Going For Broke,” Miller shares his journey through war, homelessness, and trauma.

Telling their stories despite the odds is a common thread among the 50 writers featured in “Going For Broke,” published earlier this month. The anthology delves into the many faces of poverty and economic hardship in America. Alissa Quart, Executive Director of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project, and curator of the book’s essays, wants readers to know that poverty can affect anyone, transcending race, gender, disability, or upbringing. The diversity of the stories featured in “Going For Broke” emphasizes this message. “One thing can happen and someone without a cushion can fall right through the cracks,” she said.

Alex Miller’s fight began in the South Side of Chicago in 1986.

He grew up in the Robert Taylor Homes, the largest housing project in the country — one of the 27,000 people living in buildings meant to hold only 11,000 residents. Even police felt unsafe in the barely managed towers, leaving the majority of Black residents vulnerable to the violence of gang rivalries and turf wars.

Miller’s childhood bed was kept on the floor, away from the window because of stray bullets whizzing by. “Growing up on the South Side really wears on a guy,” he said, speaking on the daily violence in an interview at the NYU Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. “Especially if you look like this,” he added, pointing to the brown skin on the back of his hand. He was wearing a 9/11 memorial bracelet around his wrist.

At age nine, he lost his best friend, Terry, in a mistaken identity drive-by shooting. Traumatized by the warzone surrounding him, Miller began to feel numb to death. “I accepted it, and in some ways, I wanted it,” he said. “I saw it as an escape.”

In high school, a path to escape presented itself: enlisting. Miller was seduced by the post-9/11 patriotism that swept the country and persistent recruiter promises of a secure future after service. “If you’re a person of color and you want to escape that kind of lifestyle, you have to do your research first,” he said, looking back with hindsight. “I didn’t.”

At 18, Miller enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

For four years, Miller served as a Navy midshipman IT Specialist on the USS Carter Hall, but it was not the escape he was promised. “I saw firsthand the misuse of American military power,” he wrote in his essay, referring to the imperialist treatment of developing countries and the harm he saw inflicted on vulnerable people. “It triggered a crisis of conscience and more trauma in my already depleted body.” In 2006, he left the military with an honorable discharge, tired of fighting and ready to return to civilian life.

He anticipated easily securing a job because of the impression he had been given by the Department of Veteran Affairs and his fellow serviceman before their discharge: that their high-tech Navy skills would be easily transferrable.

After applying to over 50 jobs including Google, Apple, and IBM, he received no offers. Eventually, Miller lost his car, apartment, and ended up homeless in Virginia, Florida, and Alabama — a common fate for African-American veterans. Despite representing only 12% of the total veteran population, 33% of the homeless population of veterans are Black, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

For the next three years, Miller couch-surfed across the South, fighting for a job, shelter, and his life. The pervasive racism of the South wore on him. After years of enduring harassment from police officers and local white supremacists, a friend offered him a place to stay in New York City. Miller was kicked onto the cold streets of New York only a month later — his friend had never revealed the expiration date on the offer.

His fight with homelessness continued in New York for two more years, a dark chapter of his life filled with sleeping under a bridge, self-destruction, and self-hatred. Frustrated by the inaccessibility of programs available at the V.A., Miller said he turned to alcohol to numb the pain and trauma he had been running from his entire life.

According to the Department of Veteran Affairs, Black veterans seeking disability benefits for PTSD are denied nearly 15% more than their white counterparts, despite having the highest rates of trauma. While living in squalid shelters, as he describes it, and struggling with addiction, Miller hit rock bottom. “I stopped doing everything,” he said. “I stopped going out, I stopped seeing people, I stopped caring.”

He finally sought help.

He began mental health treatment like therapy and other services from the V.A. He also received the Yellow Ribbon Scholarship, which helps veterans pay tuition and fees for private universities that the post-9/11 G.I. Bill doesn’t cover. The program allowed him to attend the New School to pursue his passion for writing. “I ran away from writing for a long time,” he said. “I realized that I needed to do what I was meant to do, not what I was supposed to do.”

Today, Miller lives on the Upper East Side and is an accomplished independent writer, with a keen focus on technology, gaming, and veteran rights in America. He spends his free time playing video games, going to the gym, and caring for his rescue cat, Christina.

When asked how he beat the odds, it’s hard not to notice Miller’s humility. He consistently credits the mentors who believed in him, like New School professor Sue Shapiro and his sixth-grade teacher Mr. Gatwick, who showed him kindness amidst the brutality of his childhood.

“I’m always trying to thank somebody because I spent so many years thinking that I’m the one,” he reflected. “But I’m not. I am made of everyone.”