It started with a Reddit post on the sub-community for Hololive Production, the Japanese Virtual Youtuber agency. At the time, Larry Zhao was still a budding game developer, and was posting about what he thought might be the right fighting move set for his favorite VTuber, Hoshimachi Suisei, when he was contacted by another Reddit user about the possibility of working on a Hololive-themed fighting game.

Beyond a few games he had played as a kid, Zhao didn’t know much about fighting games, and nothing about how they’re made, but he joined the team anyway. “I really liked Hololive … I thought that they were something special,” Zhao tells me. “Just the vibes that they gave, the experiences that they gave to viewers, and I wanted to create something that kind of commemorated it.”

Virtual Youtubers, or ‘VTubers’, are streamers who prefer to use an animated avatar, typically drawn to look like anime characters. The first iteration of this concept could be arguably traced back to Ami Yamato, debuting in 2011, whose model seemed to be a photo-realistic rendering of her face than what the typical VTuber model would eventually look like.

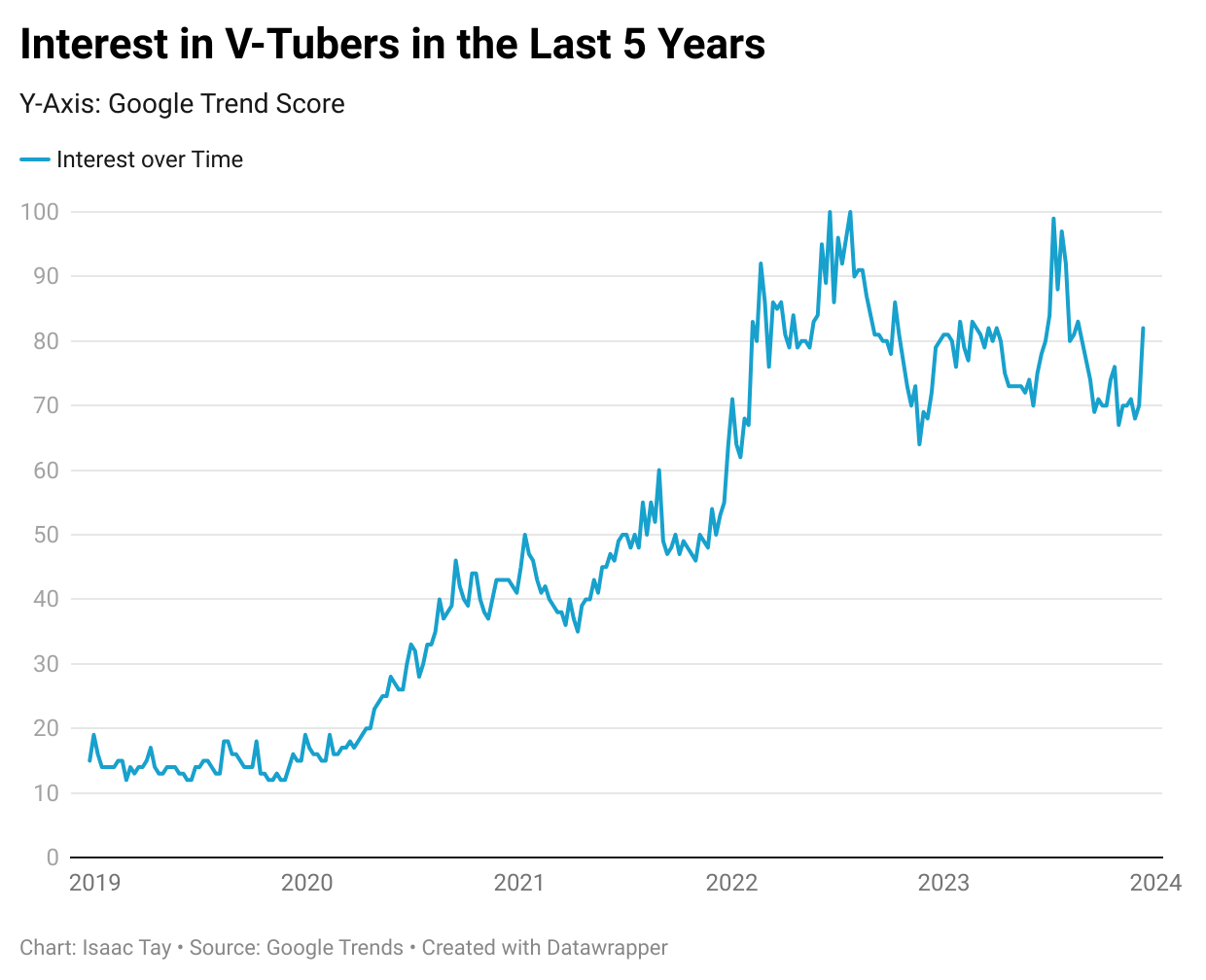

However, it wouldn’t be another five years before the term “Virtual YouTuber” would cement itself in the gaming community. And while Virtual YouTubers remain a niche interest, their popularity seems to be ever-growing with more and more VTubers emerging each year — as well as talent agencies dedicated to them, like Hololive.

The agency manages more than 60 VTubers, who are making over 300 million Yen a year, a nearly 80% increase from the previous year. In June, Hololive branched out into making games about its talents, as well as organizing live concerts, and even Expos dedicated to their clients and communities.

With the recent explosion in popularity for VTubers, fan bases have become more creative in their expressions of admiration. They post clippings, which are snippets of a VTuber’s livestream, onto social media, and share fan drawings on websites dedicated to VTubers. Some fans have even made their own games.

Zhao and his team, Besto Games, created Idol Showdown, a fighting game where you play as Hololive VTubers, all of whom have signature moves, and engage in one-on-one combat against other players. The game, released in May 2023, features 10 characters based on Hololive VTubers, as well as stages that are unique to individual creators’ “lore.” It was entirely designed in pixel art and features a 2D side-scrolling combat system. The team that worked on it was comprised of about 70 volunteers, who had contributed in various ways over the course of three years.

The characters include: Hoshimachi Suisei, a blue-haired girl dressed in a dark gray plaid blouse and cap who wields an ax, which is based on a community meme; Inugami Korone, a dog girl who wears a yellow jacket and white blouse, and who is most famously known for her endurance streams and boxing within the community; and Kiryu Coco, a dragon girl with orange hair and a purple tail who uses fire as part of her moveset.

In its opening week, the game drew in 26 Hololive members and a peak of over 10,000 players. “Back in the day, almost no one in Hololive played fighting games,” Zhao says. “We did not expect this wave of so many people in Hololive playing.” Seeing his favorite content creators play a game that he worked on was “surreal” for him. He recounted some of his favorite moments watching them play the game, including seeing Hololive’s Indonesia Branch member,Vestia Zeta (the gray-haired secret agent, and one of his personal favorite VTubers), who had no fighting game experience before winning her first competitive online match.

“Seeing yourself improving, and seeing all this work you put in practicing, trying to do things on purpose, and seeing it actually executed in a match is completely different than [practicing] in training mode,” Zhao explains. “Being able to elicit these emotions in these talents that I care about so much —it’s one of those things that reminds me why I want to be a game developer — trying to get these emotions, these experiences and packaging them into a game.”

Zhao’s first introduction to Hololive was through Minato Aqua (the pink-haired introverted maid VTuber of the group), where he saw her play Super Smash Bros in 2020. At the time, he simply saw her as part of the growing VTuber trend, having known about Kizuna Ai prior. But then, he watched a documentary on Hoshimachi Suisei on Youtube, about the rise of her career.

“It kind of told her creative story of starting off as someone who produced everything herself,” Zhao recalls. And, as someone who was on his own creative journey, Zhao could relate to Suisei. “I was like, ‘Okay, I like this.’ I wanna watch someone else who’s going on their own creative journey, trying to make an impact, trying to express themselves in the world.”

On the other hand, while the fan response to the game’s initial release was overwhelming, it was also “incredibly stressful,” Zhao says, because it was not anticipated that the game would receive so much traffic, resulting in some “crazy bugs.” But since then, as the game’s player base has cooled, Zhao tells me that he’s happy to see the community of people that has stuck around. “It’s actually interesting, because most of the people who are in now came in from the fighting community. So we have people who did not know anything about Hololive, and they just came through fighting games.”

Idol Showdown was one of more than 100 Hololive fan games released in 2023. In the last three years, there have been over 400, including Holocure, a rogue-like video game developed by Kay Yu, which was featured as one of the top free-to-play games on the popular gaming platform Steam, with over “25,000 overwhelmingly positive reviews”.

(Datawrapper/ Isaac Tay)

The community’s game developers are also pushing beyond simple but addictive ‘Flash-Like’ games –like Smol Ame, which features the mascot of Hololive’s Amelia Watson in a platformer set to the tune of her stream’s typical background music, into full-blown RPGs like the four-hour-long Hololive Councilrys RPG, a pixel-art role playing game based on Hololive’s group of the same name, ‘Councilrys’.

In addition, Hololive just recently announced their new policy to support developers of fan-made games under their “Derivative Work Game Guidelines”. Alongside this new policy, which surmises that developers will now be able to earn revenue from their games, they’ve also announced a partner program, titled “Holo Indie”, which “aims to provide an ecosystem that supports” game developers. In doing so, the company has assured developers that their games will not be threatened by copyright infringement, so long as they follow the company’s guidelines.

The first game to be made through the Holo Indie program is Holo Parade, a 2D tower defense game made by developer Roboqlo featuring Hololive talents, mascots, and fan mascots.. “I thought about what kind of game would delight current Hololive fans and also leverage my strengths,” the part-time game developer, full-time IT systems developer tells me.

Roboqlo was first introduced to Hololive in 2020 through the Minecraft streams of two of its members, Usada Pekora and Shirogane Noel. “I remember finding them hilarious and laughing a lot,” Roboqlo says. “Although my initial interest was sparked by their gaming, I truly adore them as idols as well. I am always inspired by their perseverance and effort, despite facing various challenges and adversities.”

Before they started on HoloParade’s development, Roboqlo found an outlet in creating fanart, but gradually began to want to “step up as a creator.” Realizing their skills in programming, illustration and project management could be utilized to make a game, they started work on HoloParade.

Their partnership with Holo Indie was the result of Roboqlo having proposed the idea of collaboration after HoloParade began to gain traction on social media. But because Holo Indie was still in its conceptual stages, there were extensive discussions with COVER Corp (Hololive’s Parent Company) about how to turn this idea into a reality that, nearly a year later, would be fully realized. “Even though it was the result of my own actions, everything felt like a series of miracles, and I never imagined I could come this far,” Roboqlo reflects.

“The response was far greater than I had imagined,” says Roboqlo, talking about the launch of HoloParade— which launched to over 10,000 players and has averaged around 4,000 players since, “the extent to which people played it was beyond my expectations.” Additionally, over a third of Hololive talents have played the game on stream, which Roboqlo says has been “an incredibly happy experience, both as a fan and as a creator, to have the people I admired and supported play my game and sometimes even talk about me.”

This concept of VTubing and the Fan Games that have emerged as a result come as no surprise to Anthony Dominguez, an adjunct instructor of Japanese Animation and New Media at NYU. Despite seeming like a new subculture of the larger Otaku Culture (Japanese culture that primarily relates to Anime, Manga, and Video Games), “VTubers have been around since the 90s,” Dominguez says, citing animes like Macross Plus — a science fiction mecha anime which features a virtual hologram idol or .hack//sign — an anime about characters being stuck in a virtual game and their virtual personas.

“I want to establish that, on the one hand, yes, the VTuber phenomenon is new,” Domiguez continues, “but these practices have always been around.” The difference, for the anime scholar, lies in the medium that fans have used to express their adoration for these creators.

From fan illustrations, to fan-made music videos, to conventions like AnimeNYC or Comiket, a big part of Otaku culture has always been the fan works that arise from it, and Dominguez describes fan games as what might be an evolution in fan expression.

This subculture that has emerged as a result “is an entirely new mixed medium,” Dominguez says, one that has “entrenched itself in Otaku culture already.”

Similar to Zhao, David Wu‘s first introduction to VTubers was through Kizuna Ai, which resulted in his Youtuber algorithm eventually directing him to a clip of one of Hololive’s talents — Natsuiro Matsuri and her legendary band aid story. From there, he began watching other HoloJP members like Inugami Korone and Kiryu Coco. When Hololive English debuted, he knew he was a Hololive fan.

And when the world went into lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic, Wu used the free time to learn game development and the Unity game engine — leading to his first game DOOG— a parody first person shooter based on the game Doom (1993) featuring Korone.

“When I released DOOG, I expected it to be played by maybe 100 people. It was the first game I published, so nobody knew who I was,” Wu recounts, “however, once the game went live, the number of players greatly exceeded my expectations, reaching around 2500.”

The game got so popular that Wu had to switch from a free web hosting service to a paid one, just to handle the traffic. It was this “positive reception” that motivated Wu to “develop more fangames, trying out different game genres and focusing on different VTubers, both Hololive and Indie.” And in the last three years since DOOG was released, Wu has released 11 games in total, six of them being Hololive Fan games.

“At first it was because I thought starting with an already established community would improve my visibility and accelerate my growth as a creator,” Wu tells me. “But after some time, I realized I enjoyed making fellow Hololive fans have a fun time. It became more about spreading the fun than trying to become a big name in the scene.”

“Once Hololive talents played my creations on stream, I felt like I was contributing to something larger, giving back to the talents and the community, in a way similar to how artists spend hours or days of their own time to make fanart and share it on Twitter to show their appreciation.”

Wu’s biggest release to date is a fan game called Delivering Hope — a 2D launch game where you throw Hololive English’s IRyS (The half angel, half demon “embodiment of Hope” VTuber) across the map and see how far you can go. Originally intended to be a small, two-week-long project that implemented simple programming using some fanart, it’s become Wu’s longest running project, “with over a year of development, multiple content updates and over a dozen collaborators.”

Since the release of the game, Hololive members like IRyS and others, as well as “thousands of players around the world,” according to Wu, have played the game. And it’s admittedly built up some pressure on Wu, as they await the game’s next update.

Wu has also contributed in other ways to the Hololive fan games community. For example, his website, Hologames, serves as a database of Hololive fan games that fall within COVER’s Derivative Work Guidelines.

The inspiration behind the website came about when he was working on DOOG in 2020. At the time, Wu was browsing online to see what other kinds of games fans were making, and keeping track of them in a spreadsheet. But as the months passed, he found that the spreadsheet soon reached 100 entries. “That’s when I thought, this list could be useful for other people in the Hololive fan community,” Wu explains. “I would like to shine a light on those fan games that somebody poured their time and soul into making.”

With the support of Hololive through its Holo Indie program, game developers, or those interested in learning more about game development, will hopefully find themselves encouraged to make fan games. And as the interest in V-Tubers and Hololive continues to grow, it will surely be interesting to see how fan games will continue to develop alongside this growth.