(Interview Translated from Spanish)

From 1976 to 1983, Argentina was under the iron grip of a military dictatorship infamous for its brutal human rights abuses, including torture, extrajudicial executions, and the chilling practice of enforced disappearance. During this period, military task forces operated with impunity, snatching individuals from their homes or workplaces, often in unmarked cars (usually Ford Falcons), and subjecting them to unspeakable horrors in clandestine camps.

The scale of the atrocities uncovered by the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (Spanish: Comisión Nacional sobre la Desaparición de Personas, or CONADEP) was staggering, with over 600 clandestine detention centers identified, where prisoners were subjected to torture and interrogation in secrecy. Despite efforts to bring perpetrators to justice, including the prosecution of high-ranking military officials, the wounds of Argentina’s past continue to haunt the nation.

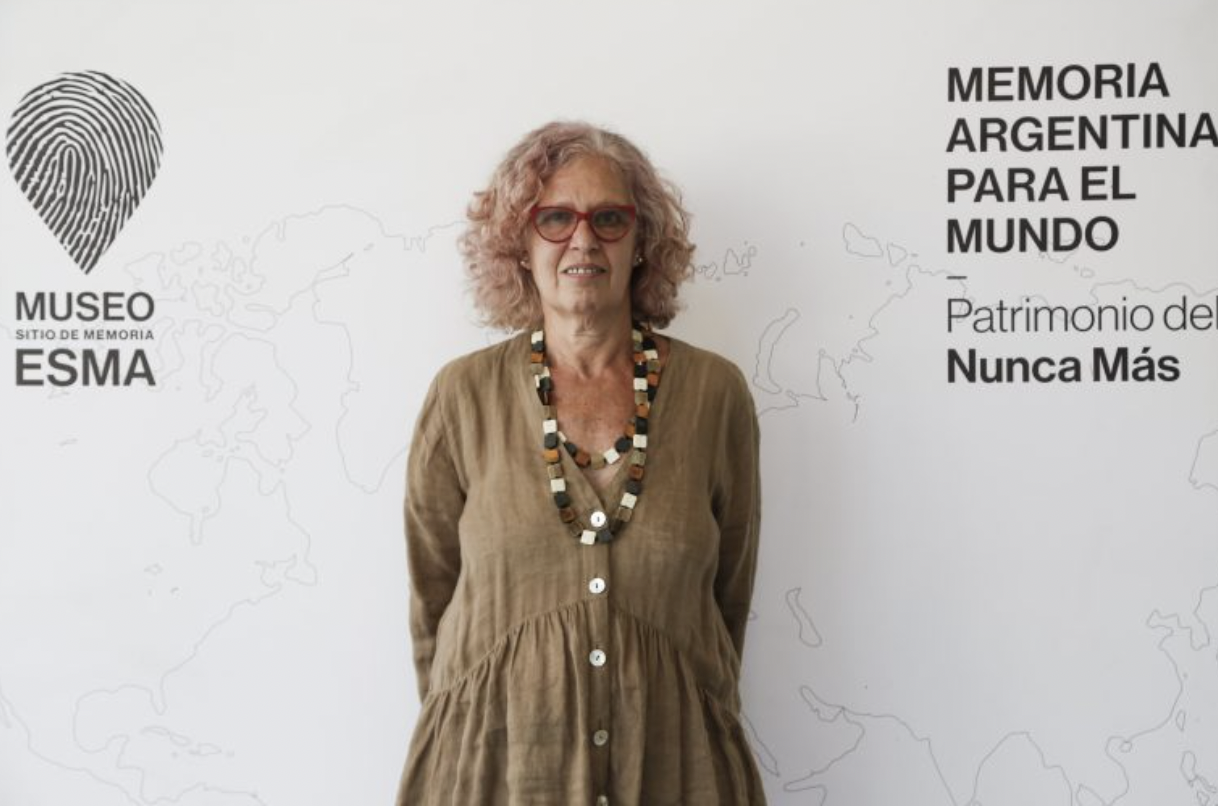

In last year’s Oscar-nominated film “Argentina 1985,” Alejandra Naftal stands out as the sole historical figure captured in the footage. At the time depicted in the film, she was a young adult who had testified at a human rights trial recounting her ordeal of being unlawfully detained as a high school student during the military dictatorship. The film is featured on Amazon Prime.

We discussed these matters through two interviews, one in Ms. Naftal’s home, and another in a local coffee shop in the oldest neighborhood in San Telmo, Buenos Aires.

Can you tell me about your political affiliation during high school?

I was born in a middle-class Jewish family in the city of Buenos Aires, where politics, culture, and art were present at lunch, dinner, and family gatherings. In the ’70s, I began my political activism as a teenager in high school in a Peronist group, called Unión de Estudiantes Secundarios. It had a “guerrilla” practice. The military part began to have more power than the political part. I began to feel uncomfortable. I didn’t like weapons, I didn’t like the danger.

Do you mind sharing your kidnapping story?

On May 9, 1978, when I was 17, they kidnapped me. A gang, a group of men, broke into my family home with weapons and put me in a Green Ford Falcon car. They began a tour of kidnappings in different homes until they took us all to the El Vesuvio concentration camp, located in the province of Buenos Aires. I remained there for three months. There were pregnant women, and young men and women. I was legally imprisoned in the Villa Devoto Prison where thousands of women were jailed, political prisoners. Among these 40 other women, I felt I was safe, and I knew the love of these companions.

What were some of the motives of the military dictatorship of 1976-1983?

It was part of a whole plan for Latin America, commanded by the empire that is the United States, to implement the neoliberal economy. Argentina, until the coup of 1976, was a country that, despite having dictatorships and these coups, was an industrialist country, with a national industry, a quite healthy economy, very strong unions, organized workers, a society with solidarity ties that fought for its rights, with students who fought for the public university, etcetera. That was the real objective of the dictatorship, to change an economic scheme where we began to be dependent. The debt with the Monetary Fund rose from one to ten million, which indebted the country.

What was your motivation to curate ESMA (Spanish: Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada; English: The Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy)?

So, when I came back to the country [after having fled to Israel for three years], I testified in the Trial of the Military Juntas in 1985. I studied museology, and my daughter was born. I worked in museums, in cinema, and communication. In the ’90s, I founded the Memoria Abierta oral archive of testimonies about State terrorism. I knew I had to link my profession to my lived experience.

Can you explain your involvement with curating ESMA from 2012 to 2022?

In 2012, I was chosen to curate the museological project of the ESMA museum. More than 5,000 men and women who are missing passed through the ESMA. Inside was a clandestine maternity hospital, and it housed the practice of death flights, where they threw people alive into the River Plate. I had prepared myself, consciously and unconsciously, for this project. Due to the characteristics of the experiences lived there, I thought that it had to be a “comfortable place for the uncomfortable and uncomfortable for the comfortable.” A space of containment for the victims, and a space that bothers those who are indifferent. After three years of hard work with the team, the museum was inaugurated on May 19th, 2015, and I was its Executive Director until 2022 when I retired.

What does the museum’s recent designation as a UNESCO World Heritage site represent, being only one of six memory sites in the world?

Being a UNESCO World Heritage Site is not a nomination that modifies the daily life of a space. Something interesting to point out is that UNESCO’s World Heritage was nominated when a government was ending, which was Alberto Fernandez’s. Let’s say, possibly, if it didn’t have UNESCO coverage, maybe the new government would close the museum. But it can’t because it’s something universal, it’s protection.

What are your aspirations and next career steps after your ESMA involvement?

I want to have a life with love, and humor to maintain my health and to be a good person. I want to be present, a present mother and grandmother. To be generous with the younger generation, people like you.