NEW YORK – The first day Reverend Matthew Burke, 67, got the keys to his apartment in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, was the first day he was admitted to the hospital. He stayed for a week, having to get two of his toes amputated on his right foot, before returning to his apartment.

Now, he’s sitting in his living room, on his white leather couch, smiling from ear-to-ear in his black robe and silver jewelry. A bracelet with “preacher” written on it in lowercase letters slides up and down his wrist.

Reverend Burke’s apartment is separated into four distinct sections: a living room, kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom. The unit was listed for $2,553, but he only pays $170 a month, thanks to his voucher: he first signed off on the apartment using CityFHEPS, a rental assistance program that helps individuals find and keep housing, in March of this year.

Due to the long waiting process, something experienced by many voucher recipients, he didn’t move in until the end of October. The day Burke was finally able to move in, he wasted no time, adding old — and new — pieces of furniture into his home. “When I was released, I came from the hospital straight to the furniture store,” he said.

One of his first purchases was a green dresser set. It holds all his clothes, including his 150 suits, all of various patterns, colors, and wear. He’s been collecting them for over 40 years.

“I went to go see the Godfather in 1972,” Reverend Burke recalled. “I watched them and saw how impeccably dressed they were, and I said, ‘I like that.’ I like the cuff links. I like the feathers and the hats. So I stuck with it.” He’s still furnishing the place, but he doesn’t see the rush, considering the place is now his own. It was hard waiting for it, especially considering his struggles with depression and other health issues. But now, Reverend Burke is just happy he has a place to call his own.

“This is my refuge,” he said. “The weight of the world has lifted off my shoulders.”

For nearly 5 million people living across the country, Burke’s accomplishment is something they too hope to enjoy one day. Housing choice vouchers are federally subsidized programs intent on lessening the burden for those who can’t pay amid a national housing crisis. Providing assistance to low-income families and individuals, vouchers pay for private market housing units to landlords on behalf of HCV recipients.

In New York City, close to 123,000 people use federally funded vouchers to subsidize their housing costs. When the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) opened their voucher application to the public after 10 years, 600,000 more people applied.

Given the growing demand, many states, such as Delaware, are working to expand their programs, adding security deposit assistance and providing recipients with support identifying a place to live. Others, such as New York, are rolling out programs like accessory dwellings units, or ADUs, and Town Center zoning, which relegalizes building above commercial ground, to provide necessary housing.

“If you’ve tried to find an apartment in New York City, it’s a huge challenge,” Winnie Shen, a housing planner for the NYC Department of City Planning, explained. “Because there simply isn’t enough housing available.”

The city has a current vacancy rate, which represents the number of unoccupied rental properties, of 1.4 percent, and that’s for all rental unit types, according to HPD’s 2023 Housing Vacancy Survey. The lack of sufficient supply of affordable housing has left many renters cost-burdened, spending more than 30 percent of their income on housing alone, according to Shen.

In New York City, 38.9 percent of renters are cost-burdened. According to data from the NYU Furman Center, the average renter households earning income ranges between $60,000 and $80,000 compared to the average poor renter household, which earns less than $15,000.

It’s why vouchers have become such a critical tool for many Americans across the country. However, multiple shortcomings – such as long waitlists, the government issuing more vouchers than available, and barriers like short time limits of 90 to 120 days – make it difficult for many to participate in the hunt for a home.

“So they [HCVs] are really, really important in the city, but really important throughout the country,” Vicki Been, former Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) Commissioner said. “And what’s tragic is one out of four, or maybe even only one out of five, [of] these individuals who qualify will ever get one. So, they’re on a wait list for years, and years, and years.”

Reverend Burke applied for his CityFHEPS voucher nearly a year ago through a social worker. He had to use his connections to public officials, police officers, and council members to get his application expedited. According to Burke, it was imperative for him to receive the voucher quickly, after struggling with his previous housing situation. He spent most of his time taking care of his 72-year-old friend, whose problems with drinking and obsessive compulsive disorder had become overwhelming. The intensity of the situation led to Burke shutting himself off from others, developing depression and meeting with a psychiatrist several times a month.

After living with a roommate in his old apartment for six years, Burke decided he needed something for himself, applying for a CityFHEPS voucher, which was a “job in and of itself,” he said.

Facing Rejection

Across the country, like many recipients, Burke faced countless challenges in securing housing. Voucher holders are routinely rejected, stereotyped, and scammed out of apartments, most commonly through Source of Income (SOI) discrimination. Although an illegal practice, many still endure such violations to their rights, but still decide to keep things moving, in fear their voucher will expire before they can finally find a place to use it.

“They wouldn’t accept CityFHEPS,” Reverend Burke said. “CityFHEPS, as far as they’re concerned, is like Section 8. Some of them may have gone through the process and saw how long it took. And they’re saying, ‘Well, I can get this person right here, and they’ll pay me right away.’”

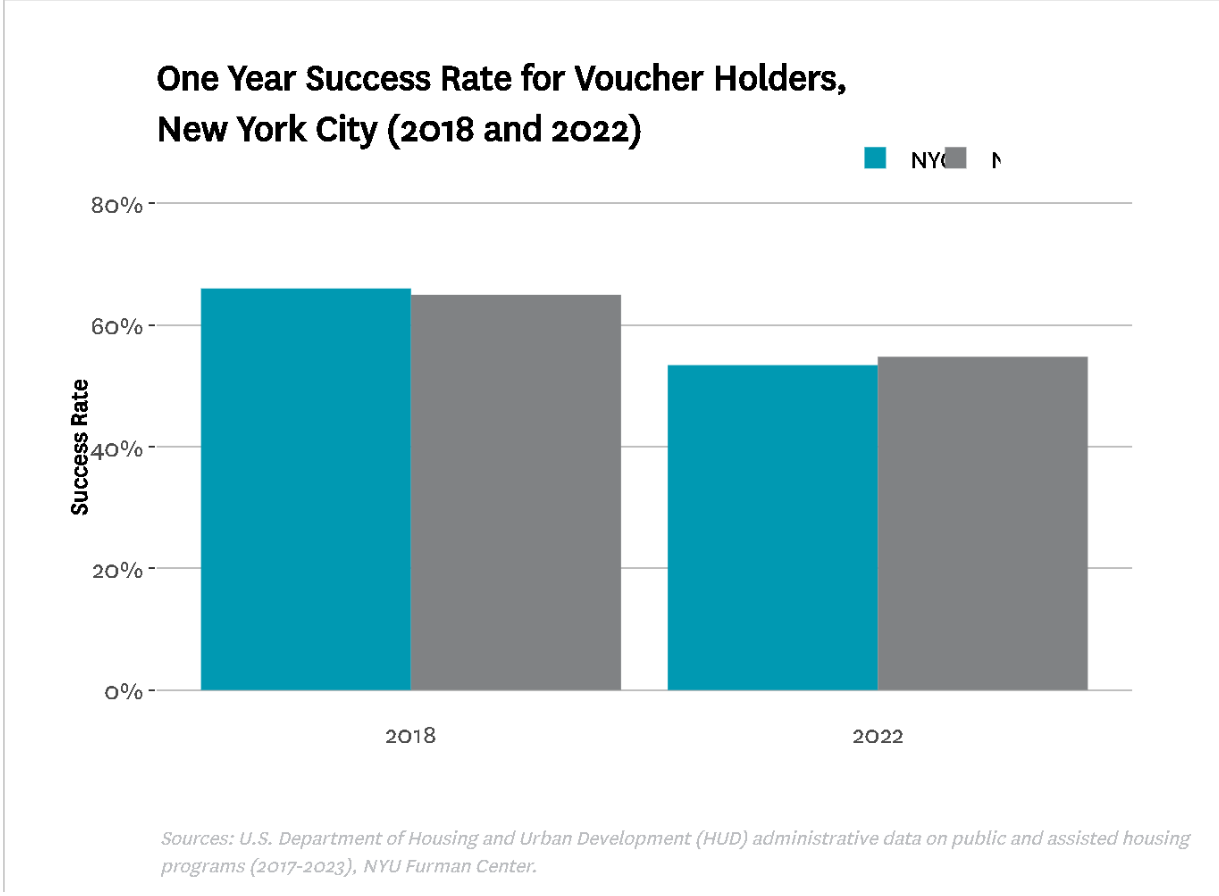

The process of securing housing for a voucher holder takes significantly longer than that of the average renter, ranging from six months to several years. In 2022, 53 percent of NYCHA voucher recipients were able to lease a home using their vouchers, and those that were successful on average searched for 171 days.

For voucher recipients, landlords will receive their money, but because the costs are covered by the federal government, and the apartment has to pass rounds of inspections before then, the checks are often delayed. Most landlords can expect to see payment within two to three months after recipients are approved.

Jessica Valencia, head of communications for Unlock NYC, a tech non-profit dedicated to helping tenants access their fair housing rights through building technology, cited other issues, including the amount of red tape and cumbersome processes.

“The paperwork process can be tedious, and it’s also because landlords don’t want the government in their homes,” she said.

The “tedious” paperwork and inspection process requires landlords to ensure everything meets federal requirements. For example, plugs have to be able to go in smoothly, the water can’t be too cold or hot, the fridge has to be able to maintain a certain temperature. Inspections do not conclude until all issues are either resolved, or planned to be, which would require the landlord to then schedule a follow-up inspection. It’s an arduous task, one that Valencia feels can alone interfere with an individual’s right to housing.

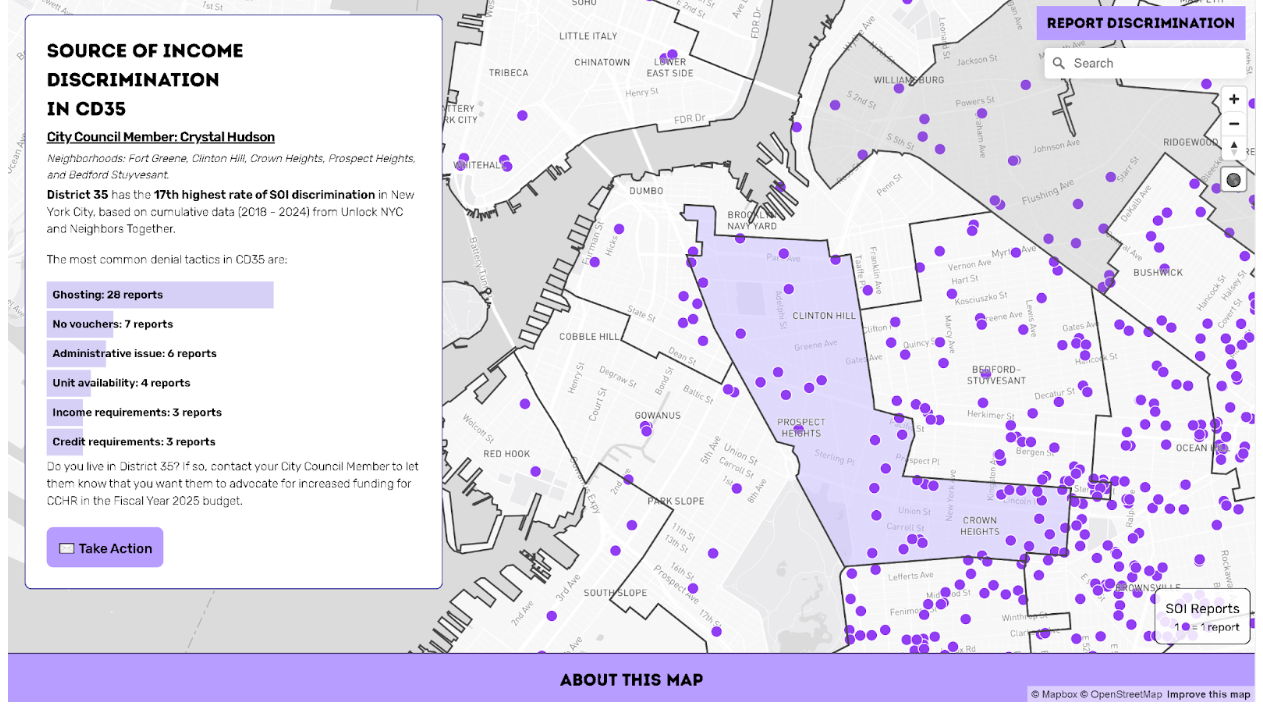

Unlock NYC released a Denial Tactics Report earlier this year, detailing the most commonly used tactics against voucher holders, which gives recommendations on how to stand up against SOI discrimination. The most common discriminatory tactics include: landlords ceasing communication after a renter mentions their voucher status; explicit denials of vouchers; temporarily taking the unit off the market or pretending it’s already been rented; and turning a renter down because of their credit score.

Burke’s Community District ranks in the 17th percentile for SOI discrimination, according to the Unlock NYC SOI mapping tool. Valencia says that, this year alone, the non-profit has received over 2,200 reports of SOI discrimination, and added the important context that those are only the ones people decided to report.

Many voucher recipients report anonymously or not at all, due to either fear of retaliation or deciding that filing such a report is a waste of valuable time. For Reverend Burke, it was the latter.

“People have various reasons why they won’t accept [vouchers],” he said. “I don’t question them. And when I see the apartment, I don’t tell them until the last minute. And I watch them switch tracks.”

It’s a reality many HCV recipients have faced and are accustomed to — but landlords are not the only issue.. HCV holders are equally likely to face housing discrimination by real estate brokers due to their status. Federal agencies like the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), NYCHA, HPD and The Commission on Human Rights are aware of these experiences, each having a section of their website dedicated to reporting housing discrimination and educating renters on their rights.

Emily Osgood, the Associate Commissioner of Housing Opportunity & Placement Services (HAS) in HPD, stressed the seriousness of such discrimination, emphasizing the agency doesn’t tolerate it in any form.

“Discrimination is a huge, huge, huge concern. If we ever hear or see, let’s say, an advertisement for a rental unit or a building, and somehow it condemns [vouchers] or only [accepts a certain] type, we immediately contact.”

Although many agencies are keeping their eyes peeled for discrimination, voucher recipients are facing another barrier: scams. Desperate for an apartment, and tired of rejection, many voucher recipients will look online, checking local listings and Facebook pages to find available units. Although such listings can appear legitimate, many are fraudulent attempts to take a person’s money through application fees.

In fact, these schemes are so common among the voucher community that Reverend Burke got caught up in them as well.

“I saw another place on Atlantic Avenue, one of the new buildings they built. It had an elevator and everything. After I responded to the advertisement on StreetEasy, they said they’d meet me in front of the building. I was talking to the person at the front desk, and I asked to see the apartment, and she said there was no apartment available here or on that floor.”

The apartment was listed twice on StreetEasy – the real estate searching tool for homes and apartments – but both have since been deleted. Both times the alleged posters set up a meeting time and place — including vacant parking lots — only to never show. Burke even enlisted the assistance of some local NYPD members to try and catch the scammers during set-up meetings, only for them not to show once again.

Many voucher recipients don’t have the connections Burke has, or might not have his experience recognizing red flags, and even if they do, trying and hoping the application is real might be better than facing continuous rejection.

“There are a plethora of individuals applying because they’re desperate,” Reverend Burke said.

The Joys of Owning a Home

At Burke’s front door is a welcome mat that reads, “CHECK YA ENERGY BEFORE YOU COME IN THIS HOUSE.” It pops against the light wooden floors of the apartment. He pointed it out, giggling when he walked past to sit down.

It’s funny to him, especially considering how much he hated his current apartment as soon as he saw it. But one piece of the place was so shocking, he had to get the apartment.

“The kitchen itself is the jewel of the home,” he said.

Burke claims he can cook anything, even saying he could give his daughter-in-law’s macaroni and cheese a run for its money. But his favorite dish will always be lasagna. Burke learned to cook from his mother. She decided to teach him some life lessons after he was constantly kicked out of school for fighting.

He refers to himself as an “eat-ist,” comfortable with anything from a peanut butter and jelly sandwich to beef bourguignon.

This apartment is important to him, and it’s why he desperately tries to give back to his community, wanting others to have a space for themselves just like he does.

“I’ve been helping people get apartments from the shelters – the women’s shelters,” said Reverend Burke. “If you’re coming out of the shelter, that’s another hurdle, because if you have a do-nothing case manager or case worker, they’ll base their thing on how they perceive you or whether or not they like you.”

He recently helped a 69-year-old woman, Erma, leave the shelter and secure an apartment. It took 10 months and she moved in at the beginning of November.

The reality is: being a voucher holder is like winning the car in the center of the mall and being told to find the key, while also being barred from entering every store. It’s tiring, according to Burke, but identifying the problem is a great start.

Charles Rudoy, Fair Housing Outreach Coordinator at HPD says more and more attention is being drawn to the barriers excluding HCV holders from having a home.

“We’re working on the city’s comprehensive fair housing plan, we have six goals, and one of them is exclusively devoted to voucher holders,” he said. “We have some commitments, part of which are actually funding some amount of millions of dollars towards enforcement of voucher discrimination.”

New York City Councilmember Chi Ossé advocated for the Fairness in Apartment Rental Expenses (FARE) Act which passed this past November and is expected to go into effect June 2025. The act would require landlords to pay broker fees for any agent representing them instead of tenants and disclose any fees in rental listings or agreements.

These are all strides in a supportive direction to minimize the burden on renters, but to Jessica Valencia, the answer goes deeper than quick solutions, it goes to the problem itself. More people need to recognize that the need for housing support isn’t limited to one type of individual, circumstance, or timetable. Anyone can be at risk of losing their home, whether that’s due to job loss or medical emergencies.

“I think in today’s world, I think anyone can be at risk of homelessness. I think the average American is one to two checks away from being homeless,” she said.