Nonprofit celebrates Italian American culture all year long, not just on Columbus Day

A fanfare, a way to take pride in something, a communal gathering — the annual Columbus Day Parade means many things to many people. Tens

A fanfare, a way to take pride in something, a communal gathering — the annual Columbus Day Parade means many things to many people. Tens

For at least a century, LGBTQ people have found bars indispensable places to meet friends and lovers, organize politically, feel safe, and let loose. But

Dozens of Ukrainians, Ukrainian Americans, and their supporters marched through the rain from Times Square to Herald Square in Manhattan on Saturday, October 7, demanding

Shortly after I entered the small, rentable gallery space nestled between Manhattan’s Upper West Side and Midtown on a moist and muggy Thursday afternoon, I

Holding a megaphone and leading the crowd, a woman chants, “What do we want?” People shout back, “Justice!” She continued, “And when do we want

The New York City Ballet Orchestra rallied for a new contract outside of Lincoln Center before the ballet’s opening performance Tuesday night. Ticket sales to

By Amelia Chang On Thursday, May 4, the New York City Ballet held their 2023 Spring Gala: Invention. The night featured the world premiere of

At a hole-in-the-wall cafe on the edge of the East Village, a wall of Asian snacks and ice creams faces a beautiful display of Italian-

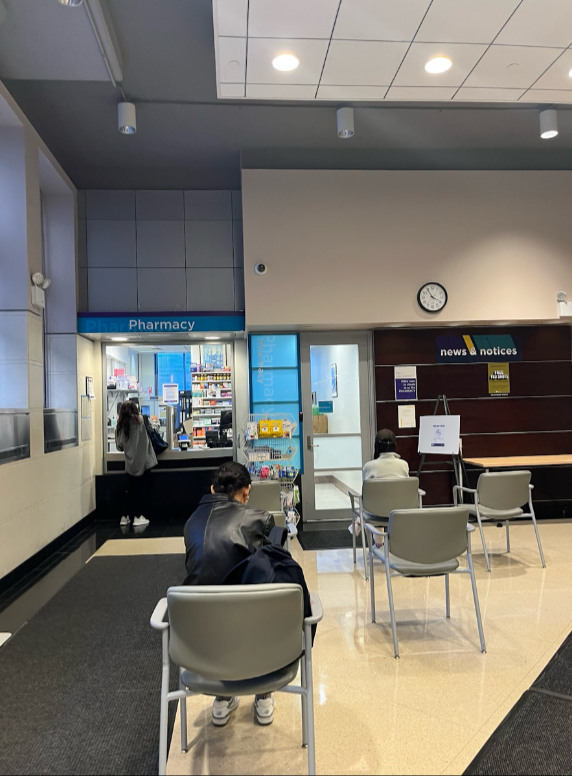

Students at NYU interviewed this past weekend were relieved to learn that abortions will now be fully covered by the university-sponsored health insurance plan starting

A pop-up show at a Brooklyn gallery this weekend highlighted women artists from across New York City. Visitors enjoyed a variety of artistic talents, shopped

CooperSquared is an online platform that highlights the outstanding work by undergraduate and graduate journalism students at New York University. The site was launched in 2016 and is overseen by the Office of Career Services at NYU’s Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute. Students do all the original reporting for stories as well as shoot and edit their own videos and photography.

Please email your story pitches to

Sylvan Solloway

Director, Career Services

sylvan.solloway@nyu.edu

Craigh Barboza

Specialist, Career Services craigh.barboza@nyu.edu

Georgia Chriselle

Aide, Career Services careerservicesjournalism@nyu.edu